The Ancient Egyptian Mummies can be seen as the ultimate example of medical advances, mythological religious beliefs, and dedication to harnessing the power of the beyond. Over thousands of years, the ancient Egyptians founded, mastered, and developed the process of mummification to preserve the body of the deceased until their time comes and they are called to stand in front of the deities of Egypt and earn their way to the field of Reeds. The ancient Egyptians practiced mummification as the ultimate means to preserve dead bodies, to ensure the deceased’s body remained lifelike and decay-resistant which involved removing moisture to leave a desiccated form that will enable the ka or soul to find the body once again in the afterlife after awakening. The ancient Egyptian mummies are able to radiate all the funerary rituals and tell the magnificent stories of great men and women.

In this article, we embark on an illuminating journey through the annals of ancient Egyptian history, guided by the presence of 45 ancient Egyptian mummies. These captivating relics, carefully selected from diverse epochs, unveil the fascinating tapestry of Egypt’s past.

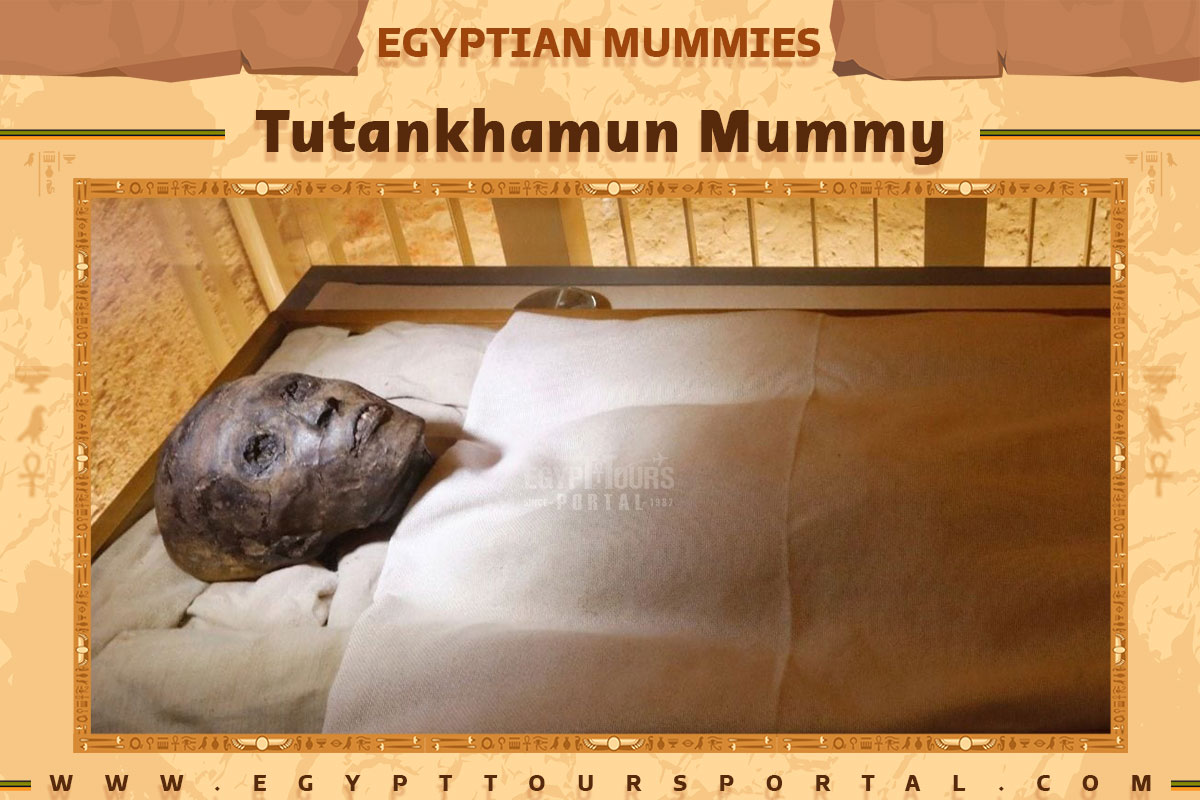

The Mummy and tomb of Tutankhamun were discovered in 1922 by Howard Carter in the Valley of the Kings which remains the last preserved tomb in all of Egypt. This discovery is by far the most recognizable which started a new wave of interest in Egyptology. His mummies are found at the Grand Egyptian Museum with his treasures.

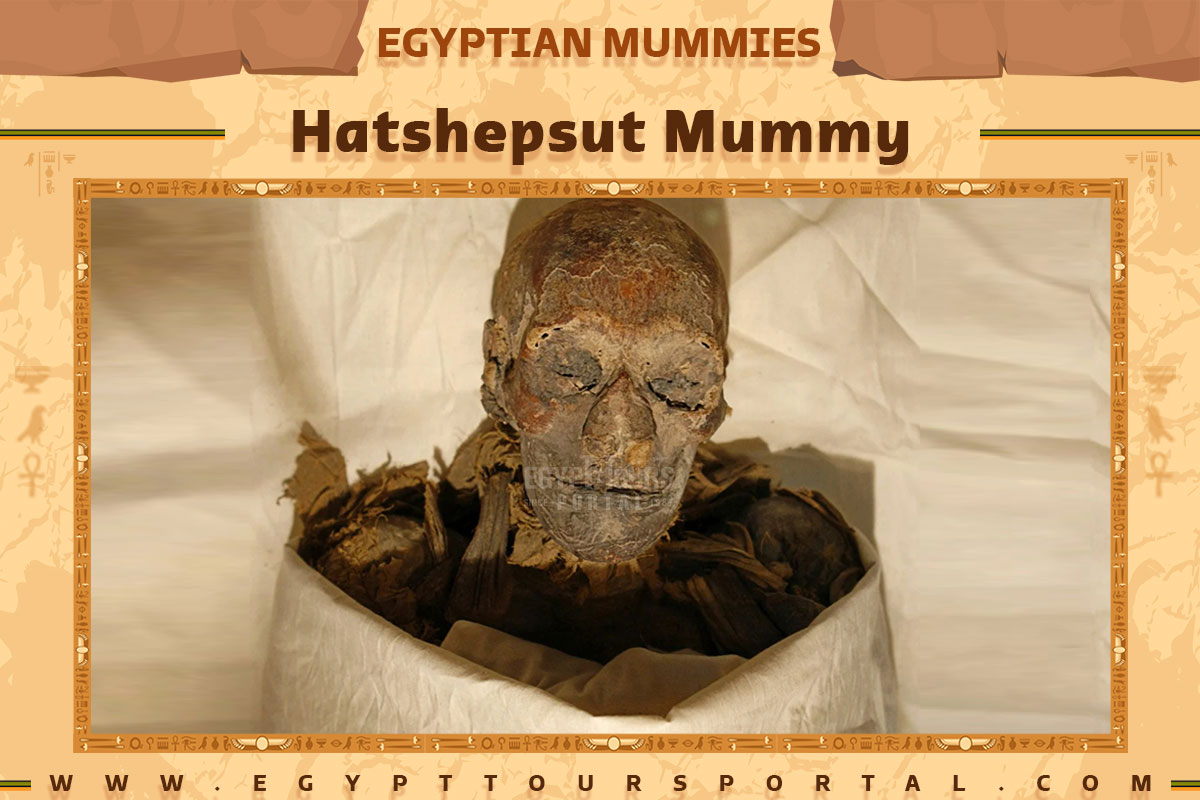

Queen Hatshepsut was buried in the Valley of the Kings which was discovered by Howard Carter in 1902 and was confirmed in 2006 by the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities and Tourism. She was located in a separate tomb containing two coffins. She was most of the most powerful rulers in the history of the New Kingdom who ruled with an iron fist as a pharaoh. Her mummies are found at the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization

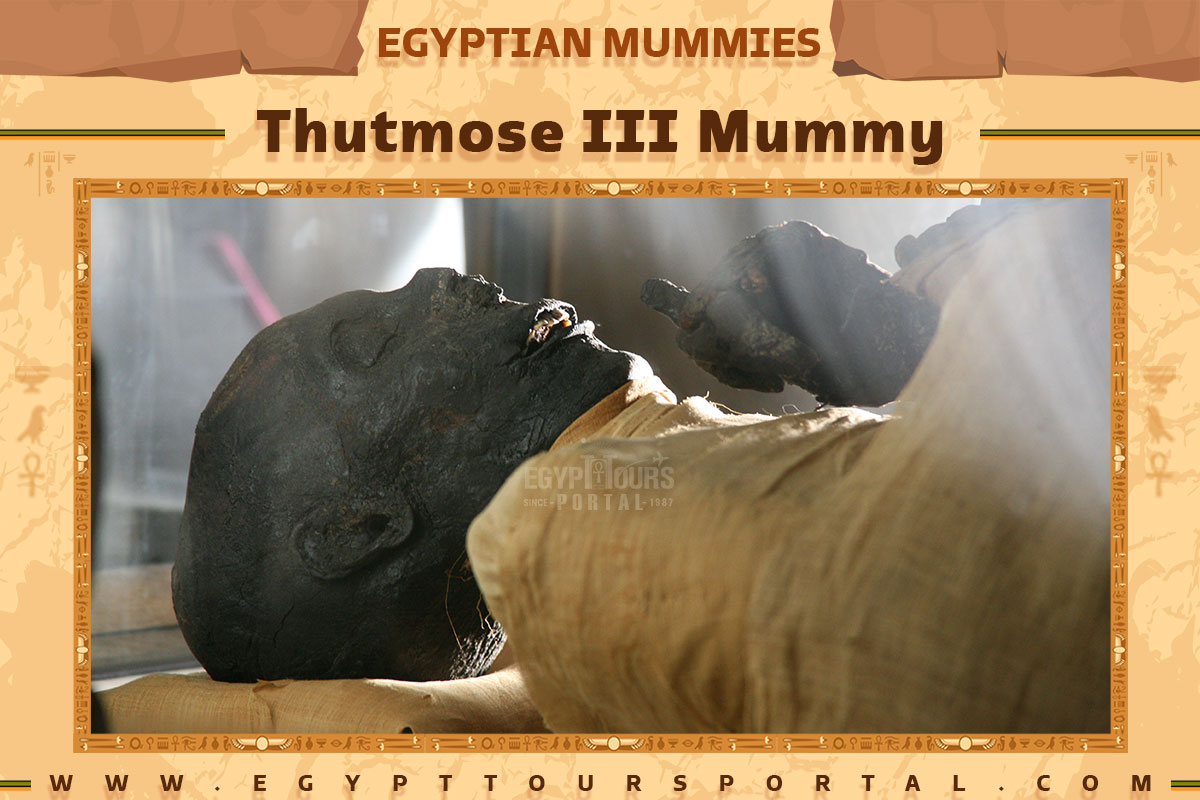

Thutmose III was known as the Napoleon of Egypt who conquered many lands won many battles, and expanded the lands of Egypt. He came to the throne of Egypt after Queen Hatshpeut and was buried in the Valley of the Kings which is now located at the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization.

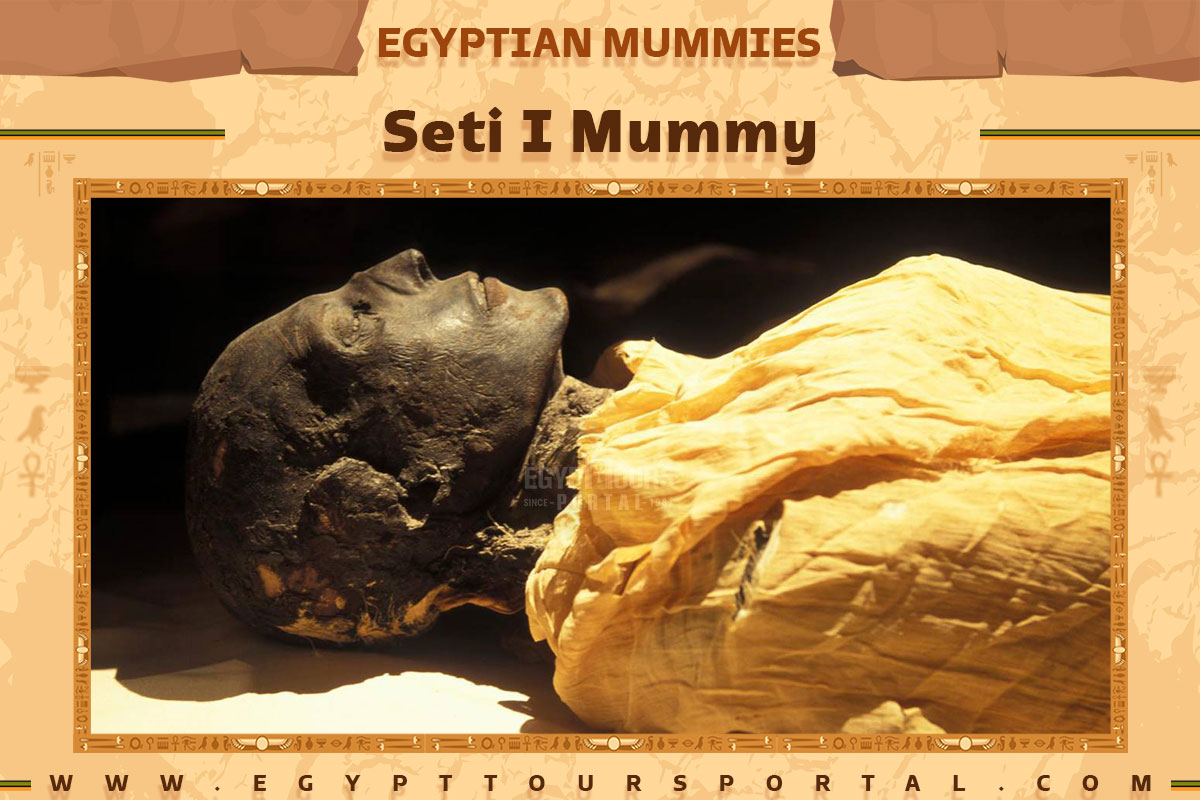

The great protector Seti I is a legendary ruler who expanded his empire fortified the entire country and made many great construction projects. His tomb is by far the finest which was found in the Valley of the Kings and his mummy was moved to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization.

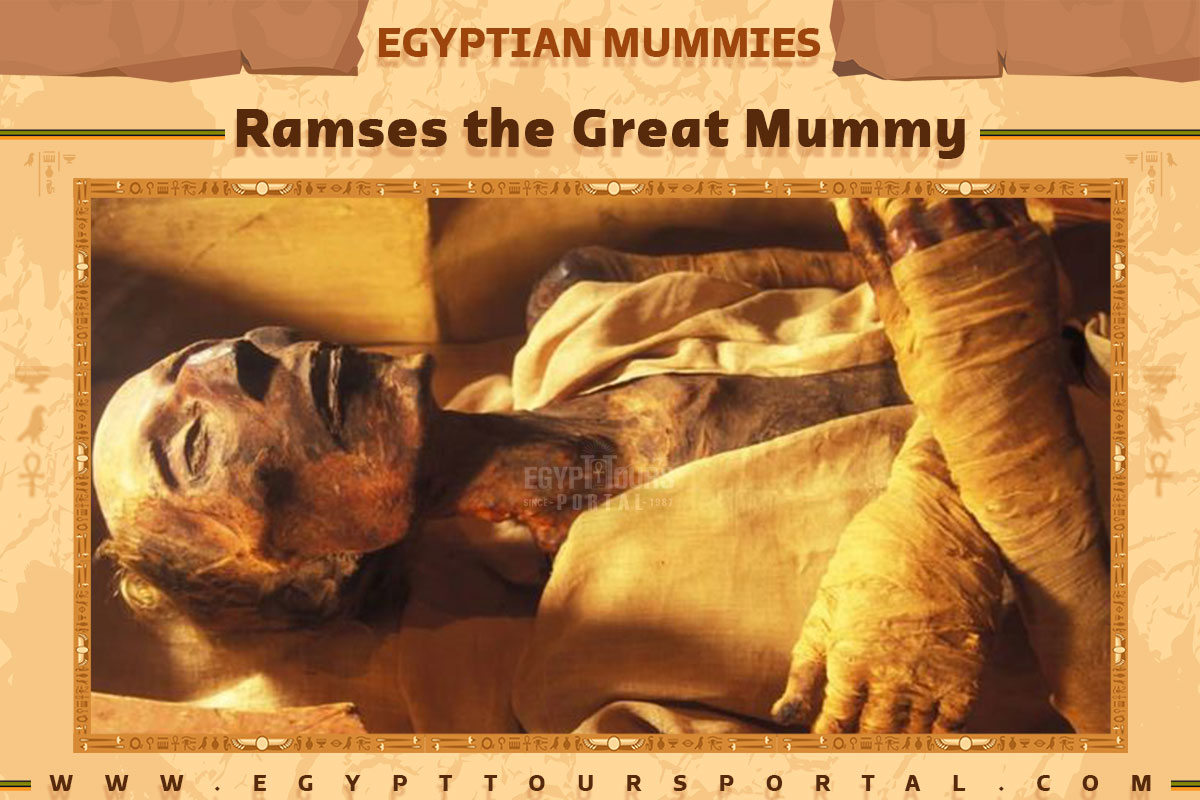

Ozymandias or Ramses II is one of the most renowned Pharaohs in the History of Egypt who won many battles like the battle of Kadesh in 1472 BC and constructed the Abu Simbel temple. He died at the age of 90 after her ruling for 60 years. His mummy and tomb were discovered in 1881 in the Valley of the Kings and it is now located at the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization.

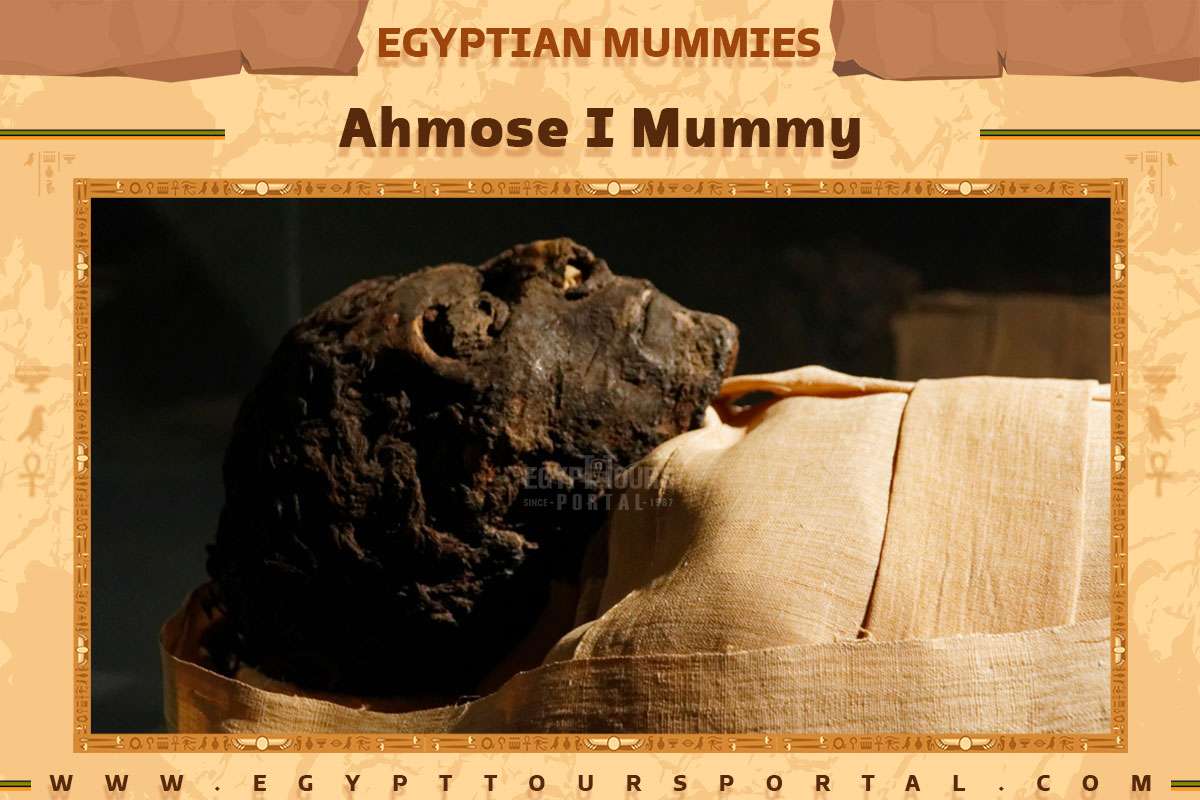

Ahmose I’s mummy was discovered in 1881 within the Deir el-Bahri Cache, alongside other leaders of the 18th and 19th dynasties. Unwrapped by the prestigious Gaston Maspero in 1886, it was located within a cedarwood coffin with hieroglyphic inscriptions. The mummy had been moved and rewrapped during the 21st dynasty, with signs of robbery. The body was about 1.63 meters (5 feet 6 inches) tall, showing a small face with no distinct features. Notably, he had slightly prominent front teeth, possibly an inherited trait within the royal family.

Maspero’s description highlighted the mummy’s resemblance to his relative, Seqenenre Tao, indicating their familial connection. Initially believed to be in his 50s, later investigations suggested Ahmose I was likely in his mid-30s at the time of death. In 1980, doubts about the mummy’s identity emerged due to craniofacial differences from both Seqenenre Tao and the female mummy Ahmes-Nefertari, traditionally considered Ahmose I’s sister. This led experts to question if the mummy was truly that of Ahmose I, leaving his true identity uncertain.

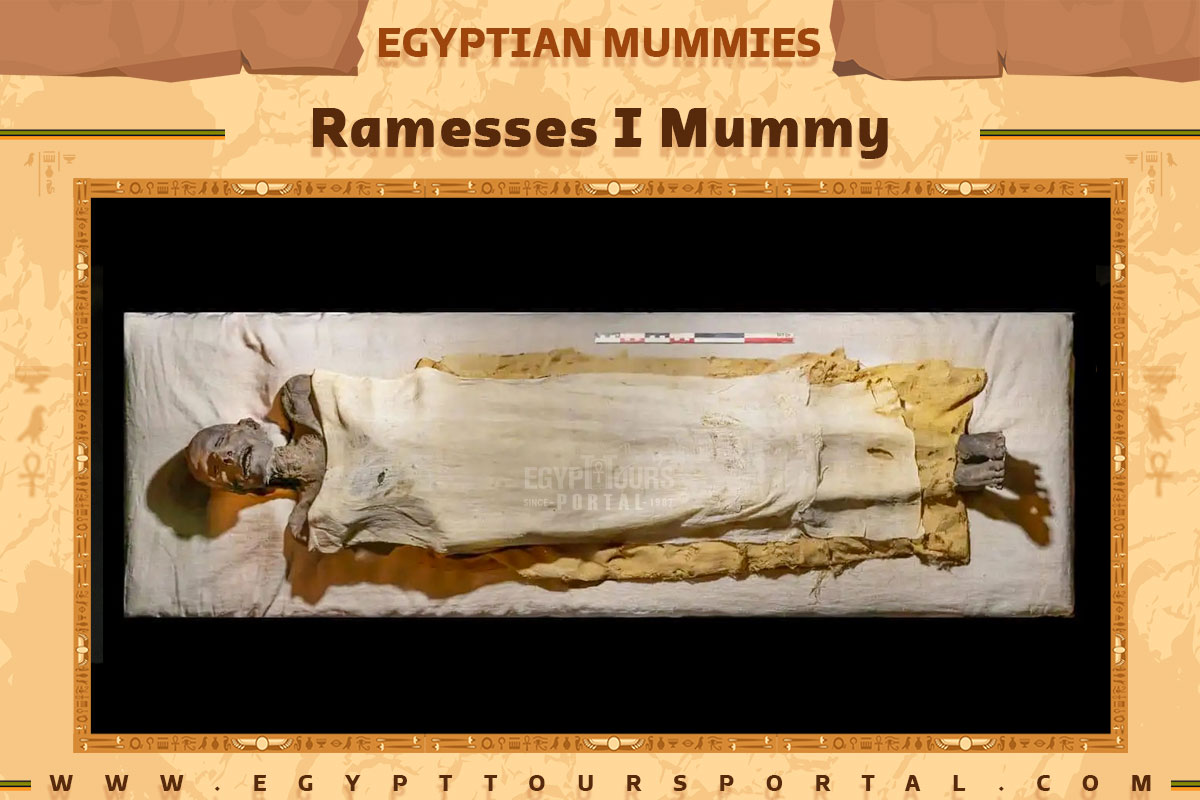

A mummy believed to be that of Ramesses I was stolen from Egypt and displayed in a private Canadian museum for years before being repatriated. Although its identity cannot be definitively confirmed, research involving CT scans, X-rays, skull measurements, and radio-carbon dating tests conducted by Emory University suggests it is likely Ramesses I.

The mummy’s crossed arms positioned high across the chest, a royal gesture reserved for Egyptian royalty until 600 BC, also supports this belief. The mummy was stolen from the Royal Cache in Deir el-Bahari by grave robbers and sold to traders from North America in the 1860s. It ended up in a Canadian museum for over a century, among other curiosities.

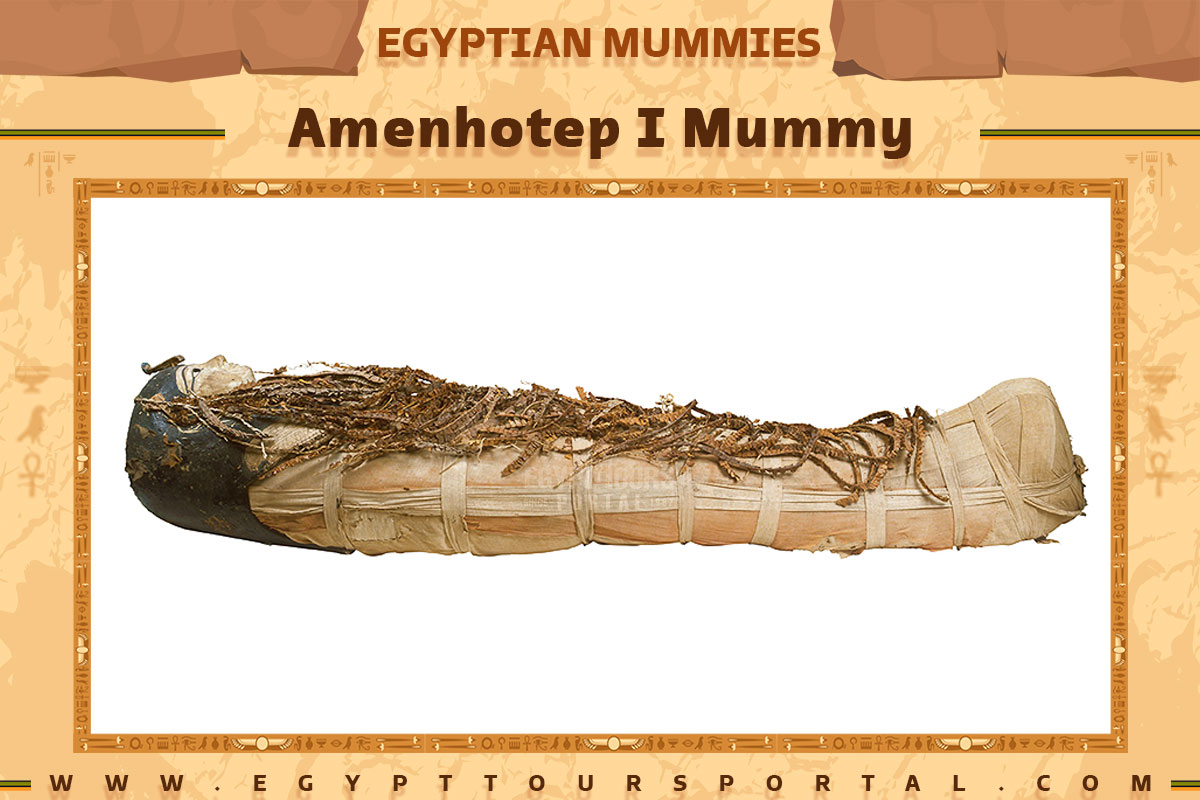

Amenhotep I’s original tomb was likely robbed or deemed insecure during the 20th or 21st Dynasty. His body was subsequently moved for safety, potentially multiple times. It was discovered in the Deir el-Bahri Cache, alongside other New Kingdom kings and nobles, during or after the late 22nd Dynasty. The cache was located above the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut. The mummy remained well-preserved, and its cartonnage face mask was carefully preserved by the priests who relocated it.

Unlike other royal mummies that have been unwrapped and examined, Amenhotep I’s mummy remains unexamined by modern Egyptologists. X-rays conducted in 1932 estimated his age at death to be between 40 and 50 years. Subsequent X-rays in 1967 suggested a much younger age of around 25 years, based on his well-preserved teeth.

In 1980, X-ray examinations of other New Kingdom Pharaohs’ remains, including Amenhotep I, highlighted similarities to contemporary Nubians. In April 2021, his mummy was part of the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade, where it was moved to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization along with other royal remains.

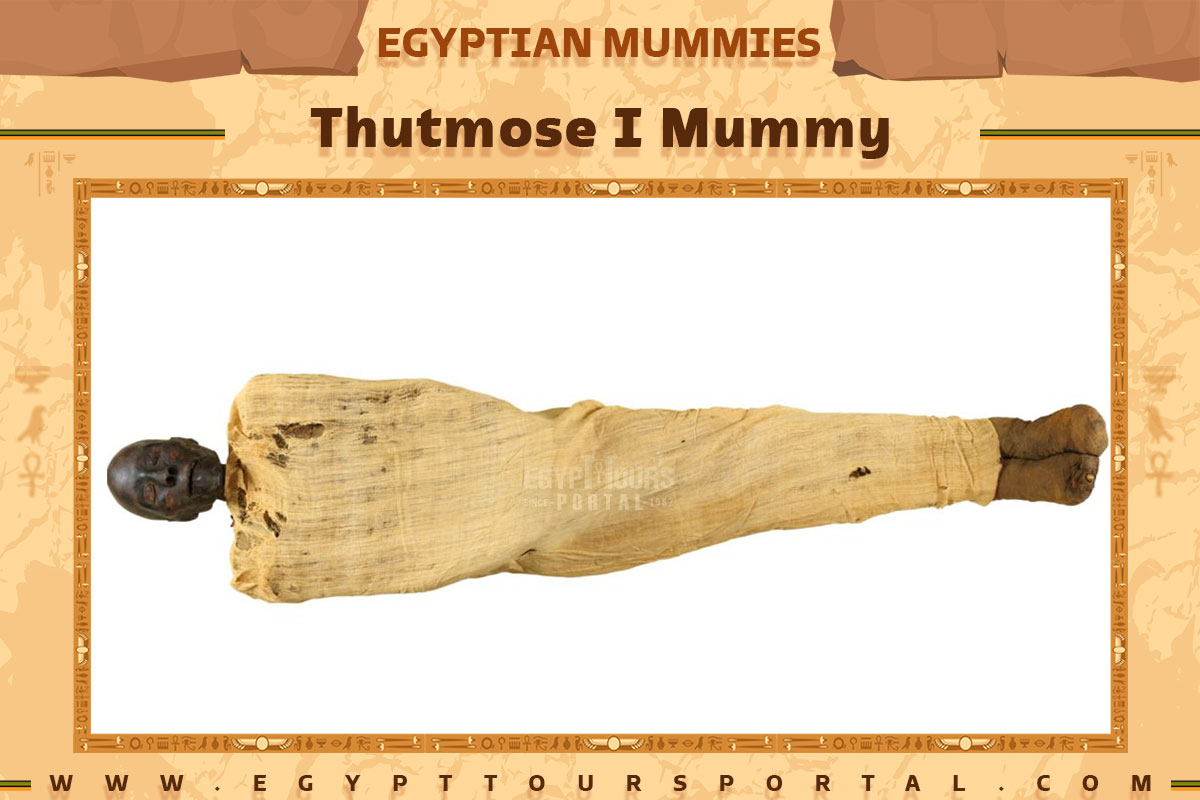

Thutmose I’s mummy was discovered in the Deir el-Bahri Cache above the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut in 1881. He was buried with other leaders from the 18th and 19th dynasties, including Ahmose I, Amenhotep I, Thutmose II, Thutmose III, Ramesses I, Seti I, Ramesses II, and Ramesses IX, as well as pharaohs from the 21st dynasty.

Although the original coffin of Thutmose I was repurposed by a later pharaoh. Subsequent examinations supported this identification due to embalming techniques consistent with the Eighteenth dynasty period. Maspero described the mummy as small and emaciated, showing signs of muscular strength despite age. in 2007, It was announced that the mummy thought to be Thutmose I was actually a 30-year-old man who died from an arrow wound to the chest, indicating it likely wasn’t the pharaoh himself. This mummy was moved in April 2021 to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization as part of the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade.

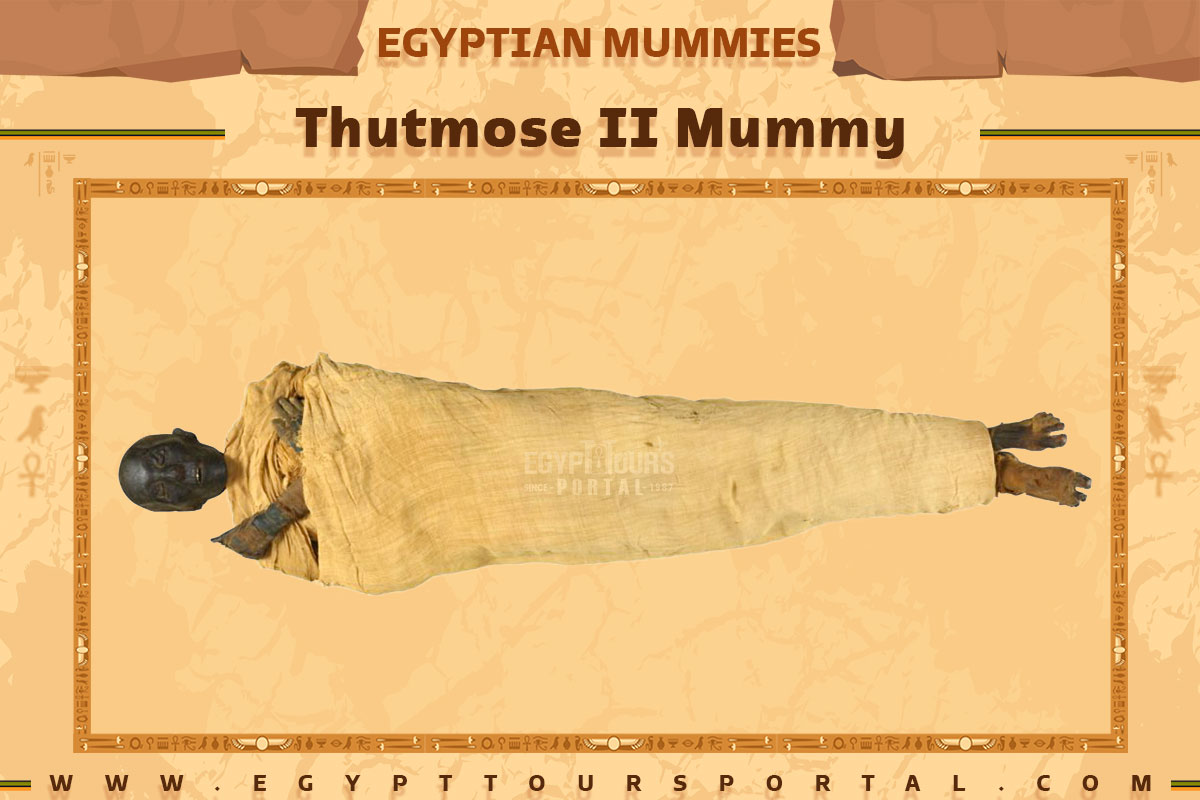

Thutmose II’s mummy was found in the Deir el-Bahri cache in 1881, among other 18th and 19th dynasty leaders. The mummy displayed signs of post-mortem damage, with severed limbs and hacked wounds, likely due to tomb robbers. Unwrapped by Gaston Maspero in 1886, the mummy strongly resembled Thutmose I, possibly his father. The body bore signs of a challenging life and a disease that embalming couldn’t hide, including scabrous patches, scars, a balding upper skull, thinness, and lack of muscular power.

X-ray studies indicated craniofacial traits common among Nubian populations. The mummy’s re-wrapping label suggested Thutmose II’s identity, but doubts emerged. The mummy was transferred to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in 2021 as part of the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade. However, its identification remains questioned, as the re-wrapping label might have been modified from Thutmose I.

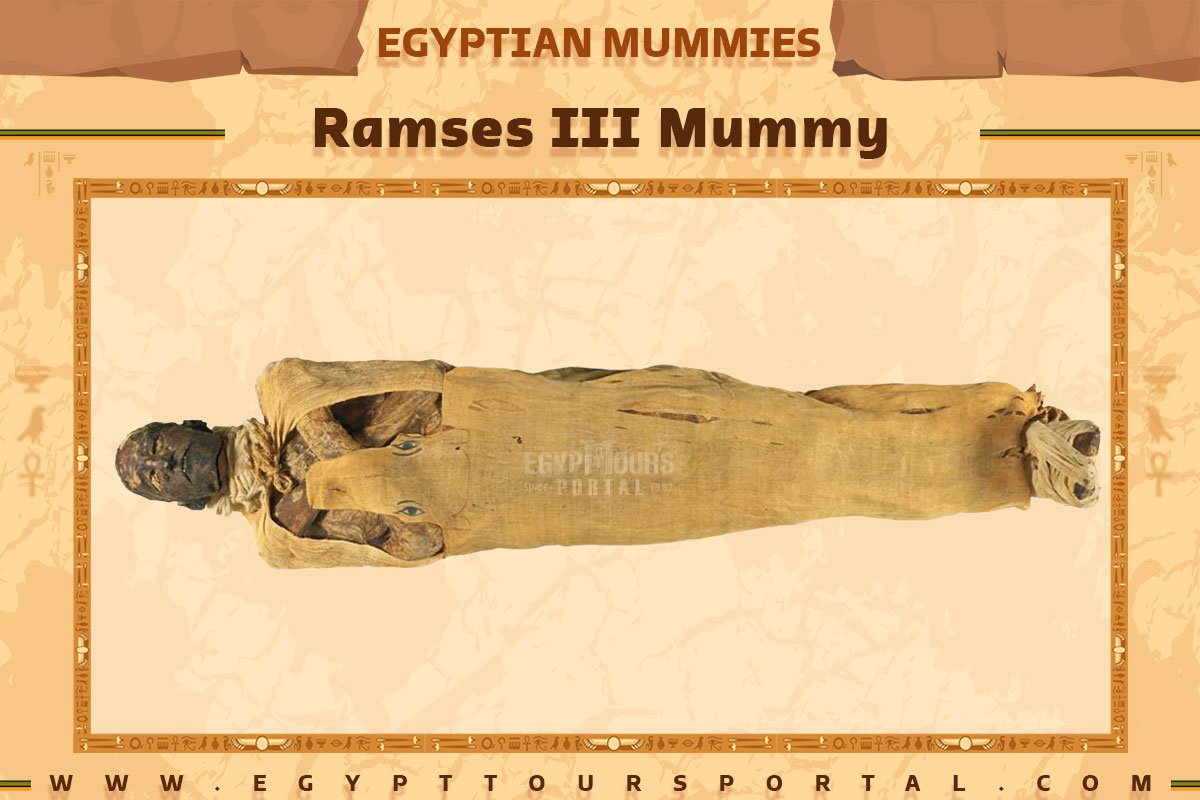

Antiquarians unearthed the mummy of Ramesses III in 1886, a find that has since become the quintessential representation of an Egyptian mummy depicted in numerous Hollywood movies. His final resting place, tomb KV11, ranks among the most expansive designs within the Valley of the Kings.

In 1980, a team led by James Harris and Edward F. Wente undertook a series of X-ray investigations on the crania and skeletal remains of New Kingdom Pharaohs, including the preserved body of Ramesses III. Their analysis unveiled significant parallels between the rulers of the 19th and 20th Dynasties of the New Kingdom and Mesolithic Nubian samples. Additionally, the researchers identified connections with modern Mediterranean populations of Levantine heritage. It was proposed that these findings indicated a mixture, as the Rammessides hailed from northern origins. A CT scan study of Ramesses III’s mummy, revealed a significant finding: his left big toe had been severed, most likely by a heavy sharp object resembling an axe.

This injury showed no signs of healing, indicating it occurred shortly before his death. To address the loss, embalmers affixed a linen-made prosthesis-like object to replace the amputated toe. Intriguingly, six amulets were positioned around his feet and ankles, possibly for magical healing in the afterlife. This newly discovered foot injury supports the theory of the Pharaoh’s assassination, suggesting multiple attackers employing different weapons.

In April 2021, his mummy, along with those of 17 other kings and 4 queens, was relocated from the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization. This event, known as the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade, marked a momentous occasion.

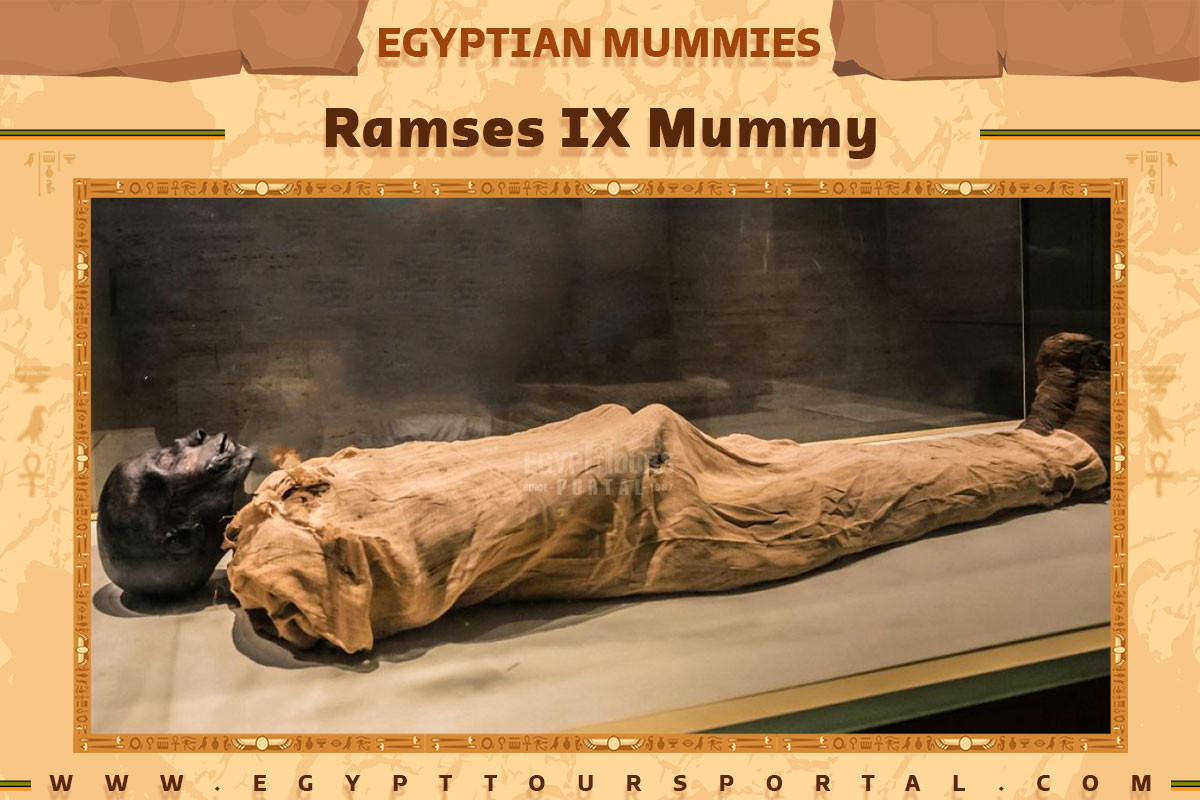

In 1881, the mummy of Pharaoh Ramesses IX was discovered within the Deir el-Bahri cache, located in the coffin of Neskhons, wife of Theban High Priest Pinedjem II. During its unwrapping by Maspero in 1912, a bandage with a reference to Neskhons from year 5 and another linen strip mentioning “Ra Khaemwaset” from year 7 were found, potentially linking the mummy to Ramesses Khaemwaset Meryamun (IX) or Ramesses Khaemwaset Meryamun Neterheqainu (XI).

However, due to the discovery of an ivory box of Neferkare Ramesses IX in the same cache and historical burial patterns, it’s likely that the mummy is indeed that of Ramesses IX. The estimated age of death was around 50, though determining mummy ages is challenging. The mummy exhibited injuries like broken limbs, a neck, and a missing nose. In April 2021, Ramesses IX’s mummy was transferred from the Egyptian Museum to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization during the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade, which included 17 kings and 4 queens.

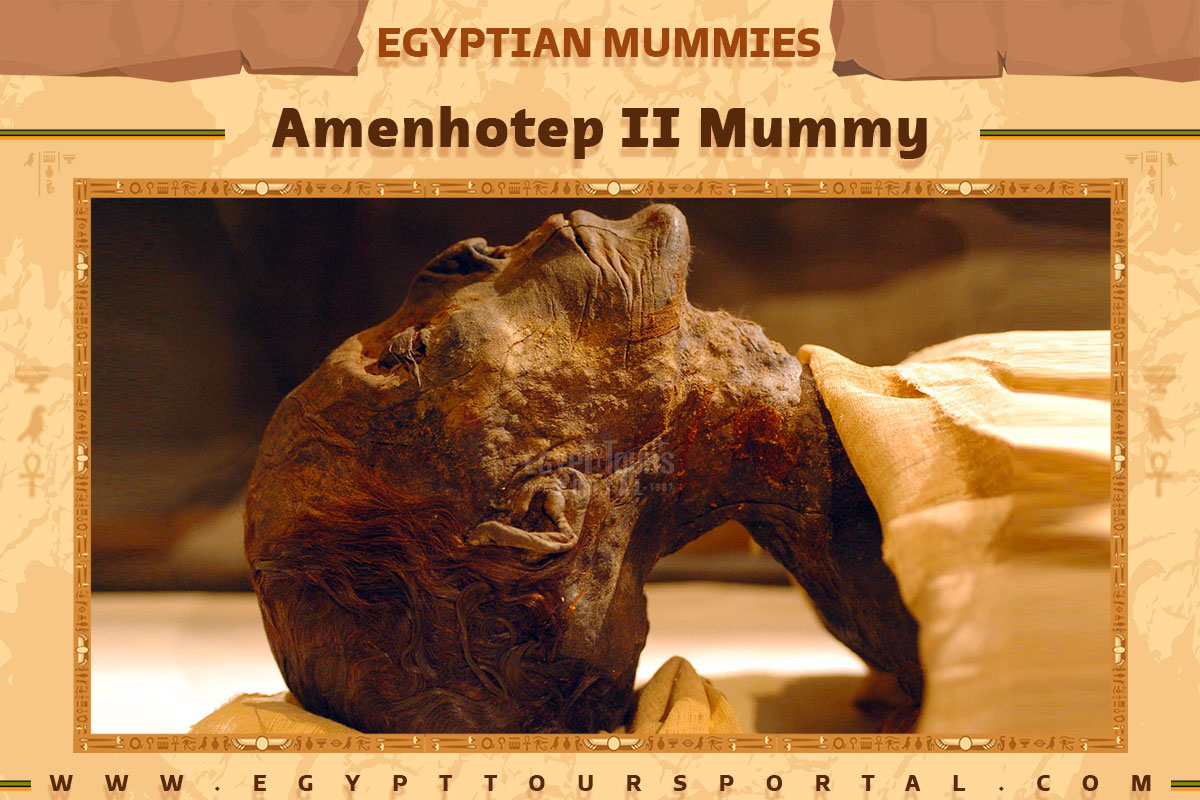

The mummy of King Amenhotep II underwent examination and documentation in January 1902 by Gaston Maspero, Howard Carter, and others. In 1907, anatomist Grafton Elliot Smith further examined the mummy, removing linen from the face to reveal a body 1.67 meters tall with white-infused brown hair and a resemblance to his son Thutmose IV. The body exhibited small tubercles, potentially from embalming or disease, and resin-preserved jewelry impressions, like a beaded collar and geometric pattern on the back. Smith estimated his age at death to be 40 to 50, based on dental wear and greying hair, but the cause of death remained unknown. The mummy is cataloged as CG 61069.

In 1980 X-ray examinations on Amenhotep II’s mummy and others from the 18th Dynasty, found resemblances to Nubians with slight variations. In April 2021, Amenhotep II’s mummy was relocated from the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization during the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade.

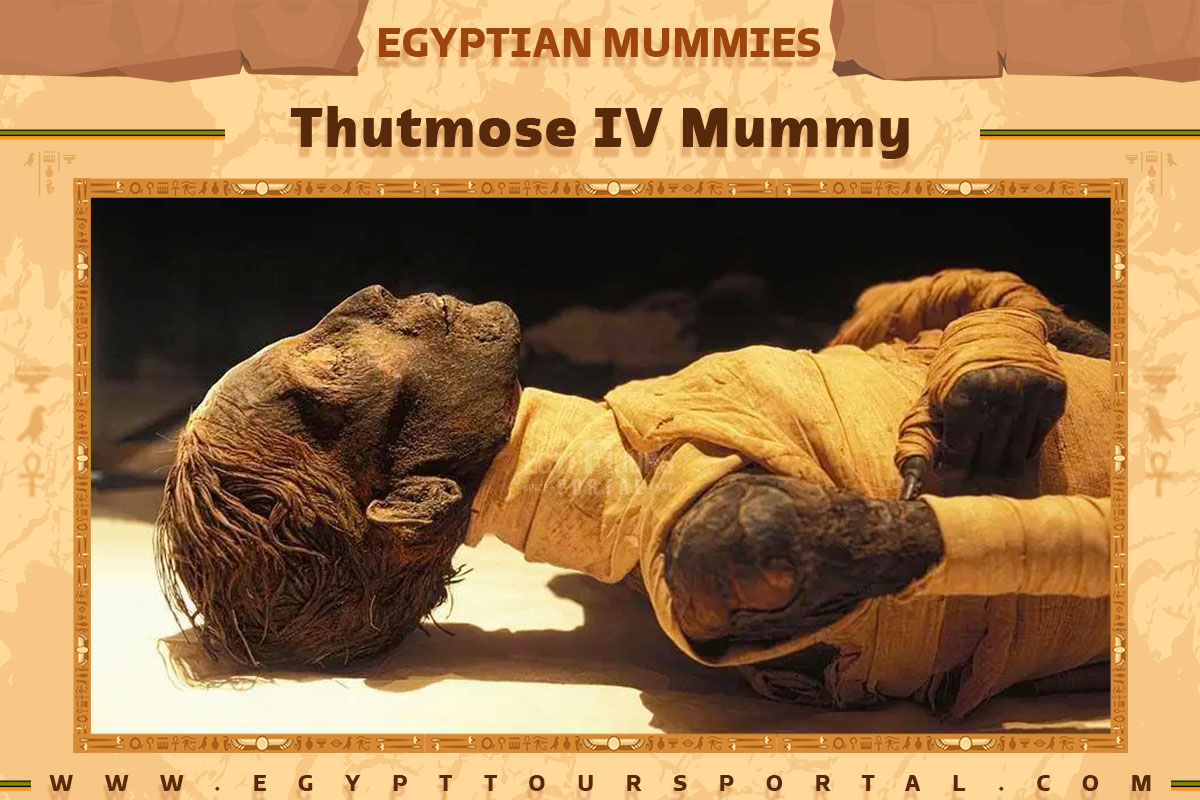

Pharaoh Thutmose IV was originally laid to rest in tomb KV43 in the Valley of the Kings, but later his body was relocated to the mummy cache in KV35, where it was discovered. Though his mummy lacked feet, his height was estimated at 1.646 meters (about 5 feet 4.8 inches), and his hair, dark reddish-brown and about 16 cm long, was parted in the middle. His crossed forearms and pierced ears were noted. his age was believed to be 25–28 years or potentially older.

In 1980, X-ray analyses on New Kingdom Pharaoh mummies, including Thutmose IV’s, found resemblances to contemporary Nubians with minor distinctions. In 2012, many studied Thutmose IV’s early demise and that of other 18th Dynasty pharaohs, attributing their premature deaths to familial temporal epilepsy. This condition could explain Thutmose IV’s religious vision mentioned on the Dream Stele, linked to epilepsy linked with intense spiritual experiences. In April 2021, his mummy was transferred from the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization during the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade.

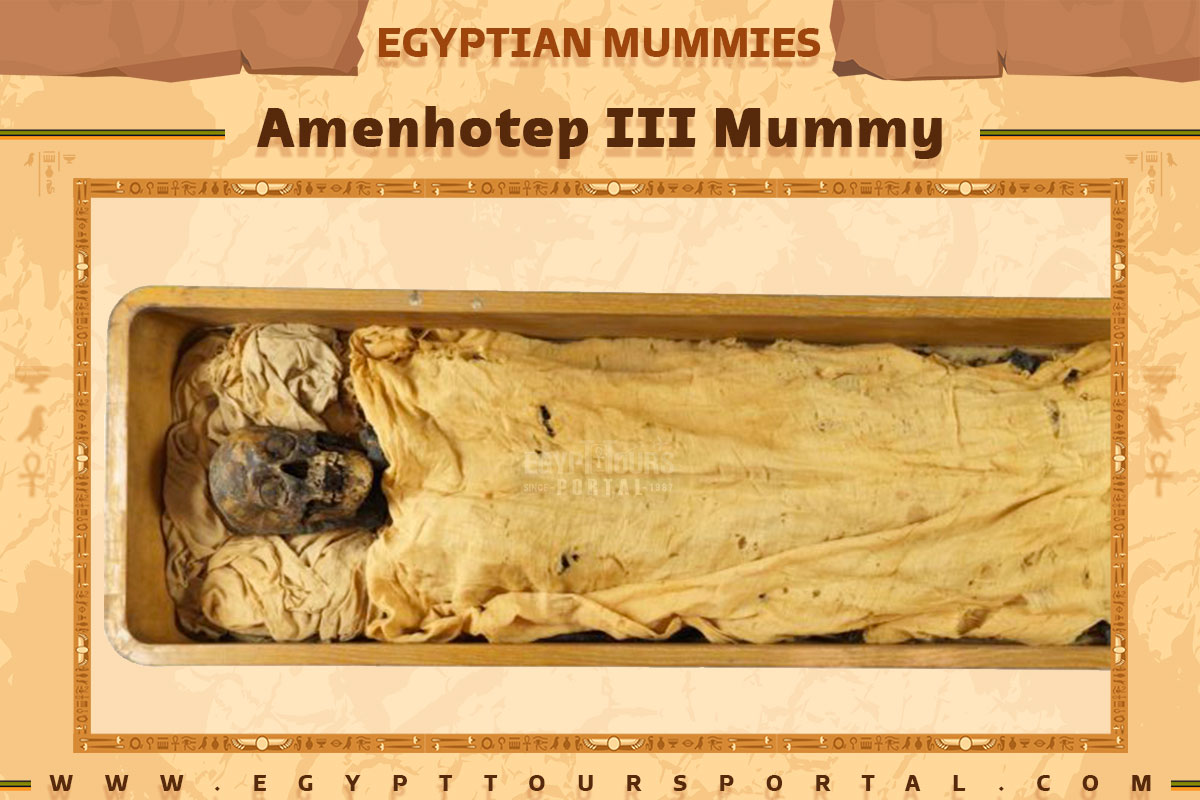

Pharaoh Amenhotep III was originally interred in Tomb WV22 found in the Western Valley of the Valley of the Kings. His mummy was later transferred, during the Third Intermediate Period, to a side chamber of tomb KV35 along with other pharaohs from the 18th and 19th Dynasties.

Notably, his mummy from the 18th dynasty exhibited an uncommon usage of subcutaneous stuffing to enhance its lifelike appearance. Initially buried in the Valley of the Kings outside Thebes, Tomb WV22 was significant in size and contained chambers intended for his Great Royal Wives; Sitamun and Tiye, although it seems they were not interred there. Subsequently, Amenhotep III’s mummy was transferred to the mummy cache in KV35 during Smendes’ reign.

In 1980, X-ray analyses on mummified remains of New Kingdom Pharaohs, including Amenhotep III were performed that noted strong resemblances between the royal mummies of the 18th Dynasty and contemporary Nubians with minor variations. In April 2021, his mummy was transferred from the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization during the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade.

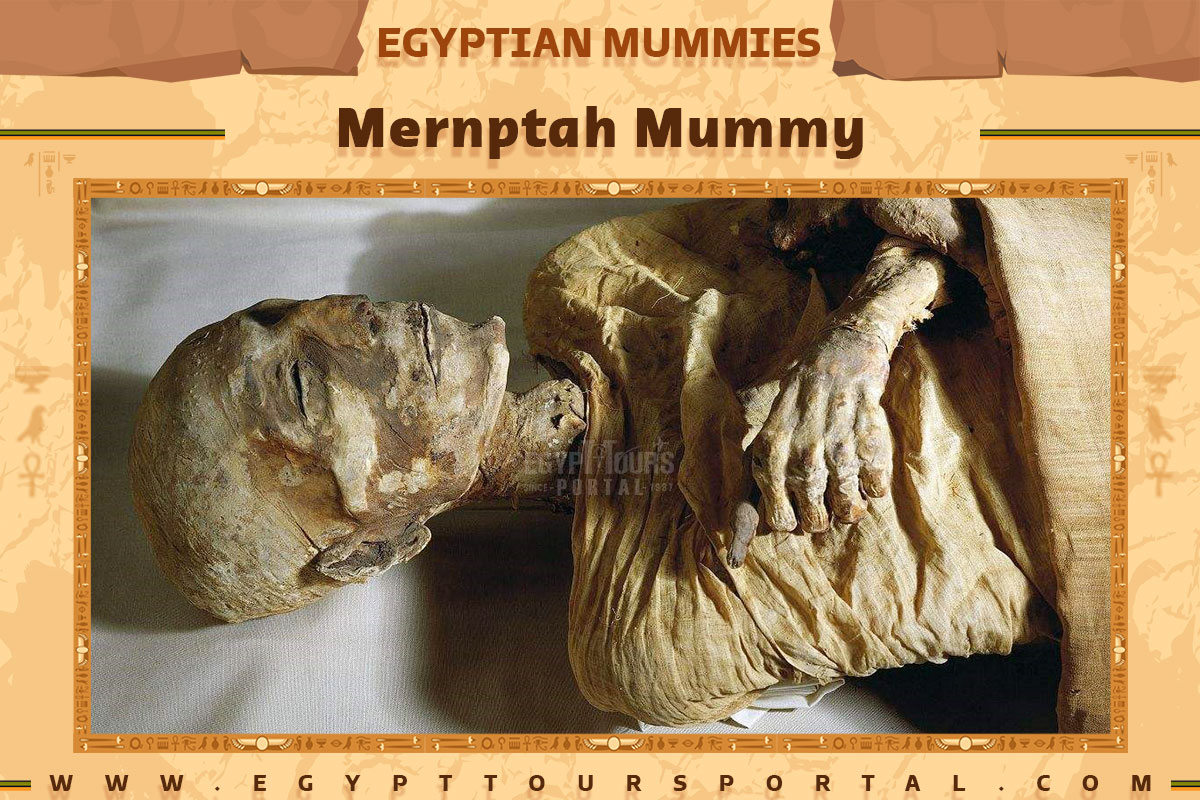

Merneptah, an ancient Egyptian ruler, experienced arthritis and atherosclerosis during his nearly decade-long reign. He passed away as an elderly individual. Initially interred in tomb KV8 in the Valley of the Kings, his mummy wasn’t located there. In 1898, it was discovered, along with 18 other mummies, in a mummy cache within Amenhotep II’s tomb (KV35). Eventually, the mummy was taken to Cairo and unwrapped on July 8, 1907. Smith’s examination revealed that Merneptah was an old man, standing at 1.714 meters (approximately 5 feet 6 inches) in height. His head was mostly bald, with a small fringe of white hair on the temples and occiput, along with short black hairs on the upper lip and closely clipped hairs on the cheeks and chin. While his facial appearance bore a resemblance to Ramesses II, his cranial shape and facial measurements were more similar to his grandfather, Seti the Great.

In 1980, X-ray analyses on the cranial and skeletal remains of New Kingdom Pharaohs, including Merneptah’s mummy were conducted and their findings highlighted notable similarities between the rulers of the 19th and 20th Dynasties and Mesolithic Nubian samples. They also observed connections with modern Mediterranean populations of Levantine origin. Harris and Wente suggested that these resemblances indicated a blend of northern origin among the Rammessides. In April 2021, his mummy was transferred from the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization during the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade.

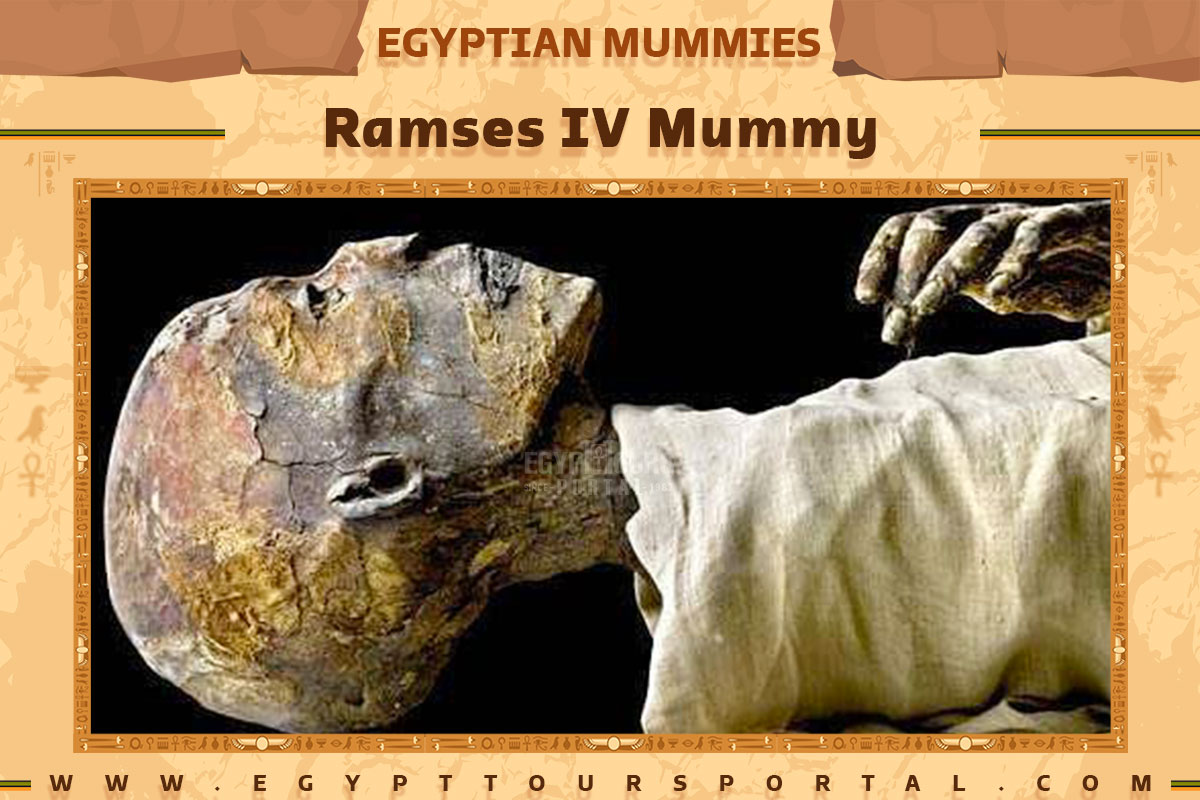

Following a brief reign lasting approximately six and a half years, Ramesses IV passed away and was laid to rest in tomb KV2 located in the Valley of the Kings. His mummy was discovered in the tomb cache of Amenhotep II’s KV35 in 1898. His primary spouse, Queen Duatentopet or Tentopet, found her final resting place in QV74.

His throne was subsequently taken over by his son, Ramesses V. Initially, a tomb designated as QV53 had been constructed in the Valley of the Queens for Ramesses IV. In April 2021, his mummy was transferred from the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, joining the remains of 17 other kings and 4 queens as part of the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade.

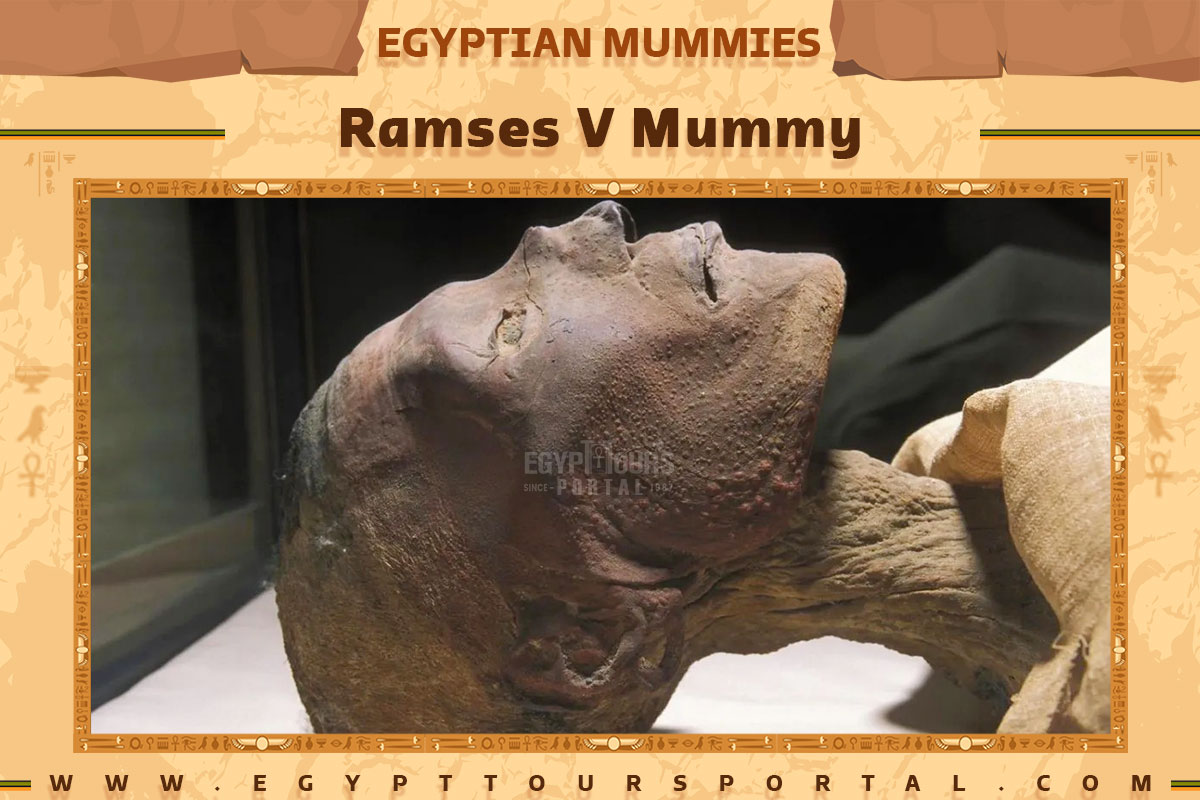

Ramesses V’s death circumstances remain uncertain, though his reign lasted nearly four years. An unusual fact is that he was buried only in the second year of Ramesses VI, which deviated from Egyptian tradition dictating a king’s burial within 70 days of their successor’s reign. In 1898, Ramesses V’s mummy was found, displaying facial lesions suggesting he suffered and potentially died from smallpox.

This condition made him among the earliest known victims of the disease. While a 2016 study traced smallpox’s shared ancestral form to 1580 AD, it mainly demonstrated that strains of smallpox eradicated in the 20th century emerged around the late 16th century, during a period of rising human movement, population expansion, and increasing inoculation and vaccination practices.

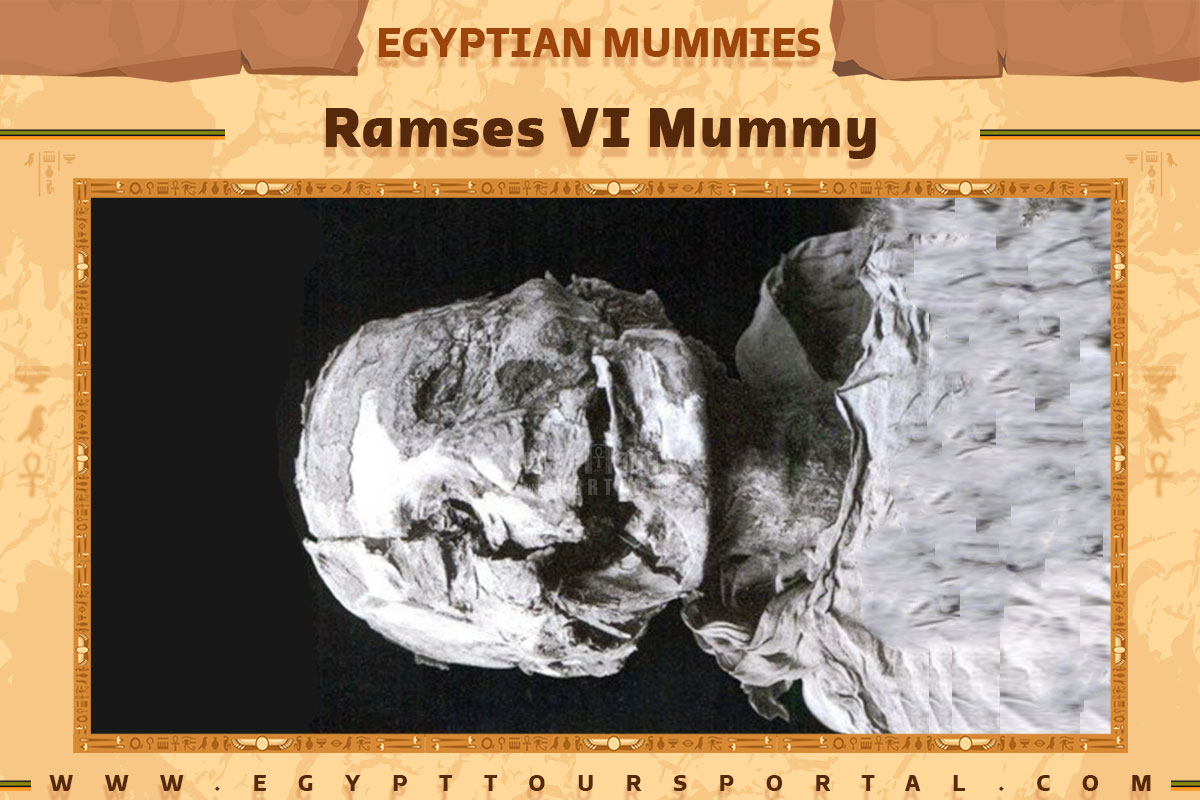

Pharaoh Ramesses VI was interred in the Valley of the Kings, specifically in tomb KV9, Ramesses VI’s mummy was relocated to Amenhotep II’s tomb (KV35) during the early Twenty-First Dynasty, discovered by Victor Loret in 1898. Medical analysis revealed he died around age forty and suffered severe body damage, including fragmentation of the head and torso due to the tomb robbers’ axes. In 1898, researchers uncovered fragments of a large granite box and pieces of Ramesses VI’s mummiform stone sarcophagus.

The sarcophagus face, now in the British Museum, was restored in 2004 after meticulous work on over 250 recovered fragments. Despite efforts, requests to return the sarcophagus face to Egypt were unsuccessful. In 2020, the Egyptian Tourism Authority released a comprehensive 3D model of the tomb, featuring detailed photographs, available online. In April 2021, Ramesses VI’s mummy was transferred from the Egyptian Museum to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, as part of the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade, alongside 17 other kings and 4 queens.

In 1980, a series of highly revealing X-ray examinations were conducted on the cranial and skeletal remains of New Kingdom Pharaohs, including the mummified remains of Seti II. Their analysis revealed significant similarities between the rulers of the New Kingdom’s 19th and 20th Dynasties and Mesolithic Nubian samples.

They also identified resemblances with modern Mediterranean populations of Levantine origin. researchers proposed that these findings indicated a blending of populations, considering the Rammessides’ northern origins. In April 2021, Seti II’s mummy was relocated from the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in an event known as the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade.

Ahmose was laid to rest in tomb QV47, situated within the great Valley of the Queens. This tomb is believed to be the earliest one constructed in that valley. It features a relatively simple design, comprising a single chamber and a burial shaft. Positioned within a marvelous subsidiary valley named the Valley of Prince Ahmose, her burial place is marked.

Princess Ahmose’s mummy was uncovered during the excavations made between 1903 and 1905. Currently, her mummy is housed at the Egyptian Museum in Turin, Italy. Alongside the mummy, They discovered several funerary items, including a segment of her coffin, fragments of linen inscribed with roughly 20 chapters of the Book of the Dead, and leather sandals. All these artifacts are preserved in Turin.

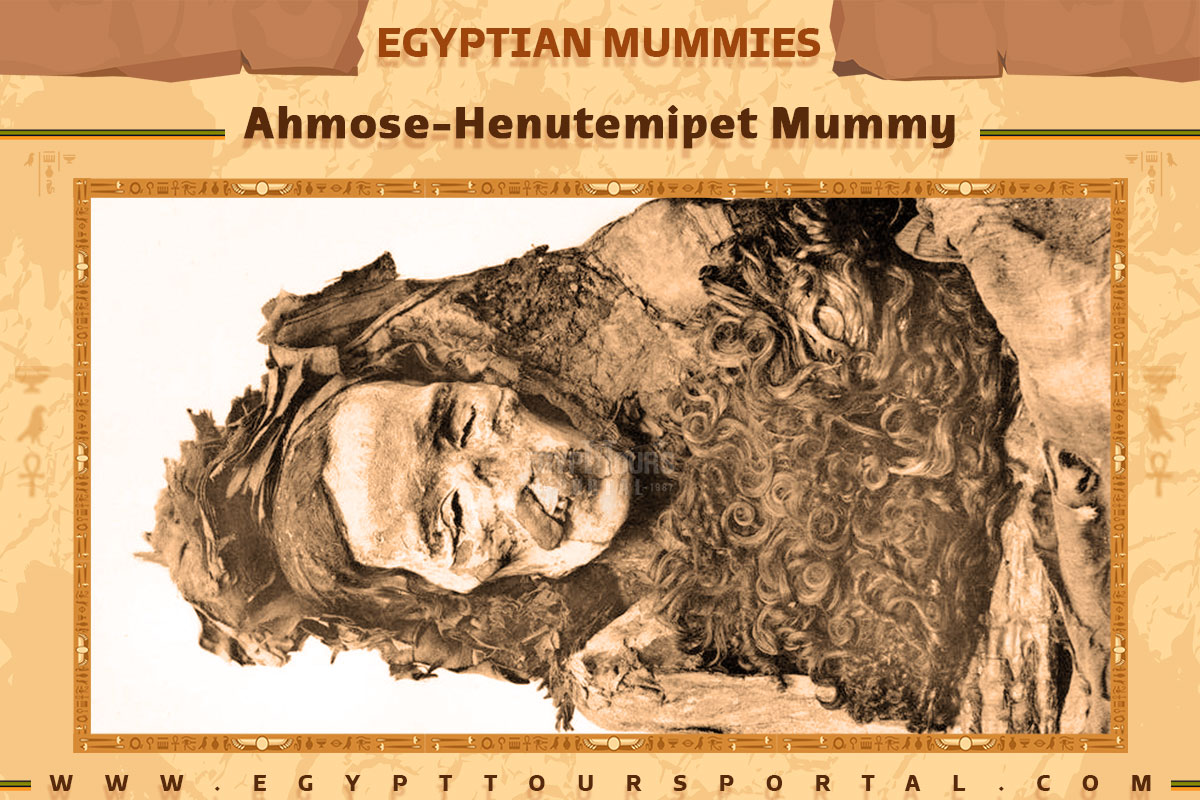

Ahmose-Henutemipet was a princess from the late 17th Dynasty of Egypt who was the daughter of Pharaoh Seqenenre Tao and Queen Ahhotep I, plus Ahmose I’s sister. She held the titles of King’s Daughter and King’s Sister.

Her mummy was discovered in 1881 and was examined in June 1909, revealing that Henutemipet died in her old age, displaying worn teeth and grey hair. Unfortunately, her mummy had been damaged, likely due to tomb robbers. It’s probable that the mummy was relocated to tomb DB320 after the 11th year of Pharaoh Shoshenq I’s reign.

Ahmose-Henuttamehu’s mummy was found within her own coffin in her tomb in Deir el Bahri in 1881. Gaston Maspero examined it in December 1882, revealing that she died as an elderly woman with worn teeth. Her mummy’s bandages bore quotes from the Book of the Dead. It’s likely she was interred alongside her mother.

After Year 11 of Pharaoh Shoshenq I’s reign, her mummy was moved to her tomb along with other remains. Ahmose-Henuttamehu is honored among the ancestral figures revered in the Nineteenth Dynasty. She’s depicted in the tomb of Khabekhnet in Thebes, positioned as the fourth woman from the left in the top row. The depiction includes Prince Ahmose-Sipair and other prominent figures.

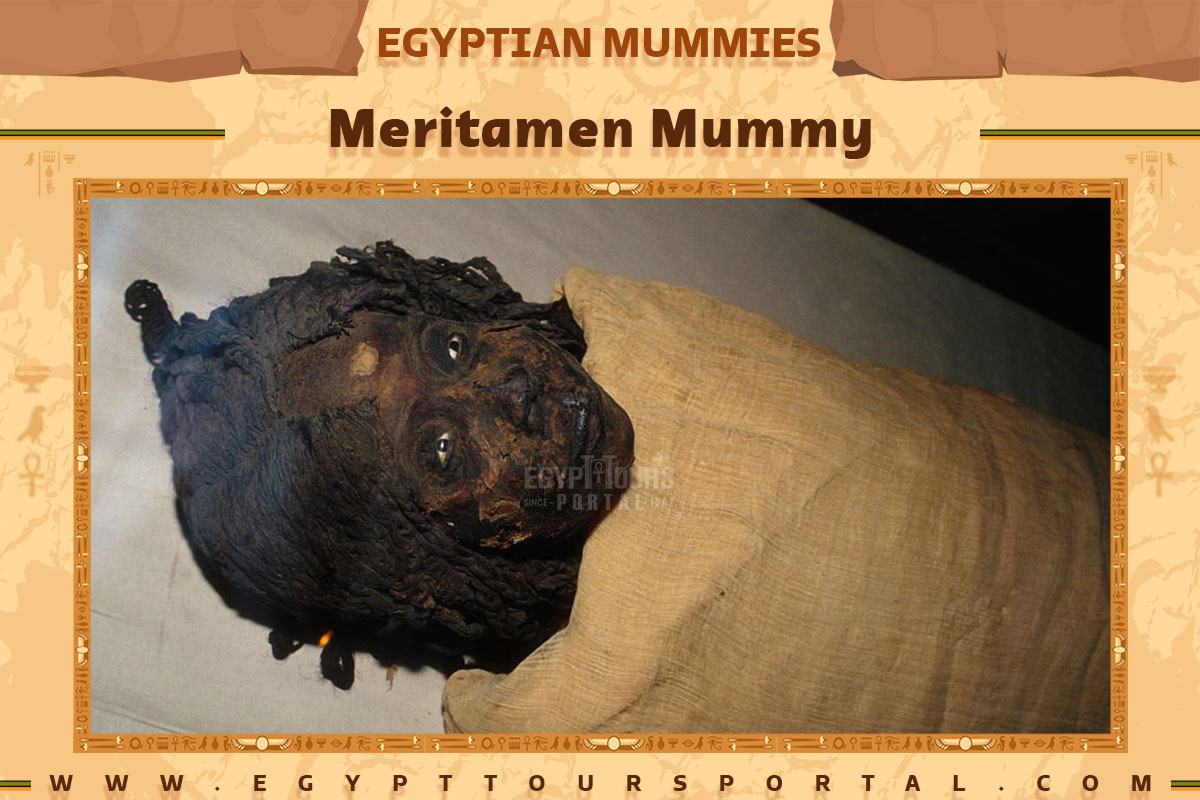

The mummy of Ahmose-Meritamun had undergone meticulous rewrapping during Pinedjem I’s reign. Inscriptions reveal that the linen employed in this reburial was crafted in Pinedjem’s 18th year, and created by the High Priest of Amun, Masaharta, who was Pinedjem I’s son.

This reburial process occurred on the 28th day of the third month of winter in Pinedjem’s 19th year. In April 2021, her mummy was transferred from the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, marking the occasion known as the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade.

Queen Meritamen was the daughter and wife of Ramses the Great, She held many religious and royal titles, famous for her limestone statue found at the Ramesseum plus she appeared on the walls of the Abu Simbel temple with her family. Her mummy is found at the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization.

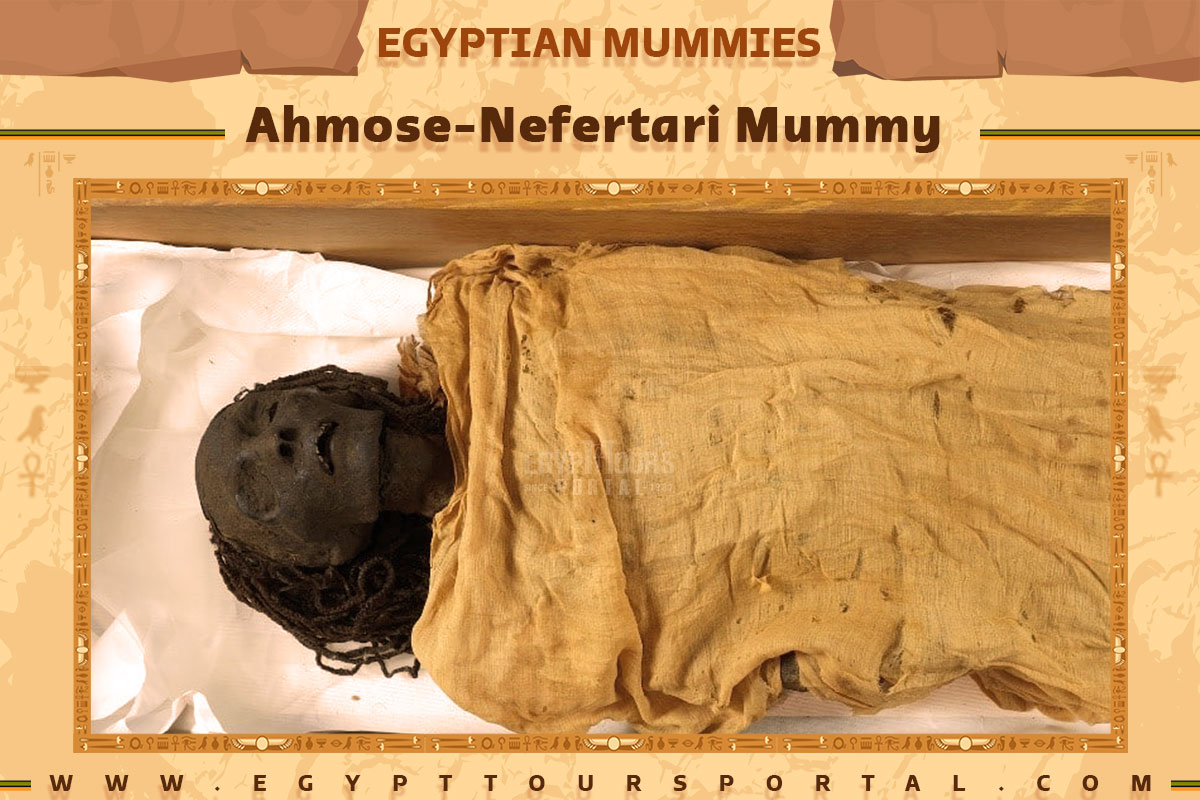

The grand wife of Ahmose I and mother of Amenhotep I of the 17th dynasty. Her mummy is found at the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization.

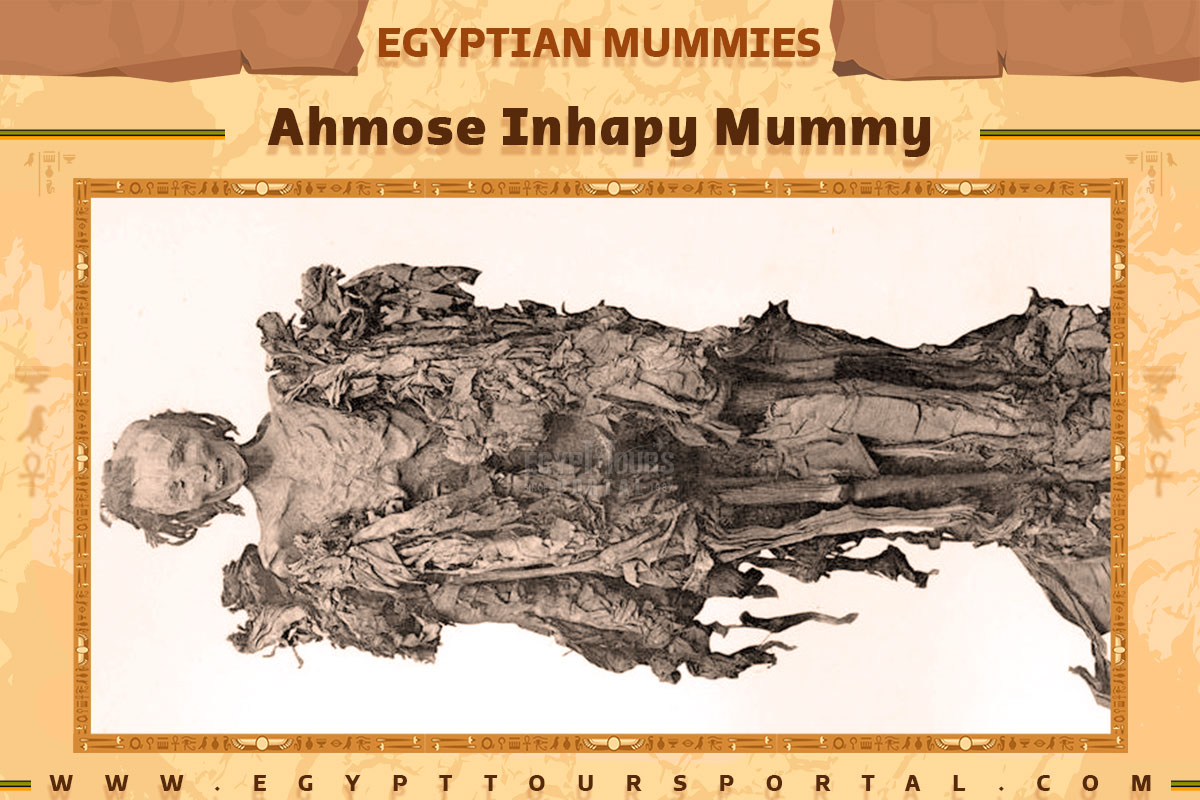

The mummy of Ahmose Inhapy is found in Thebes in Deir el Bahari where its discovery occurred in 1881. The mummy was located within the outer coffin of Lady Rai, who served as the main nurse of Inhapy’s niece “Queen Ahmose-Nefertari“. Gaston Maspero unwrapped the mummy on June 26, 1886. Inhapi is depicted as a robust, sturdy woman bearing a striking resemblance to her brother. It is estimated her burial to have taken place during the later years of Ahmose I’s rule.

The mummy featured a floral garland around the neck and was positioned with arms at the side. Notably, the mummy’s dark-brown skin retained an outer layer without any salt evidence, potentially differing from traditional preservation methods described in historical accounts. An incision on the left side suggests organ removal, possibly treated with natron, while aromatic powdered wood was scattered on the body before wrapping it in resin-soaked linen.

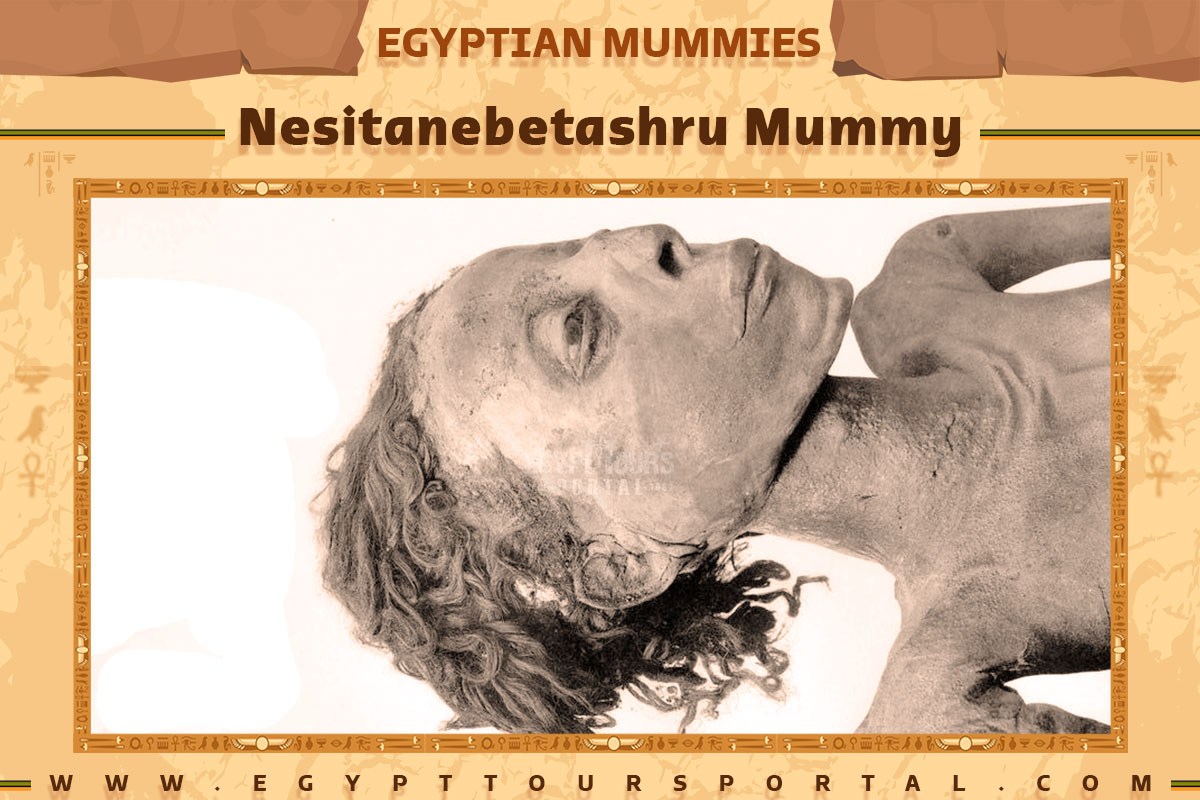

The name Nesitanebetashru pertains to two ancient Egyptian women associated with the title “Belonging to the Lady of the Ashru” which refers to the crescent-shaped sacred lake around solar goddess temples, specifically Mut. Nesitanebetashru from the 21st dynasty was the daughter of Pinedjem II who acted as the High Priest of Amun, and Neskhons. She’s cited in her mother’s funeral text inscribed on a wooden tablet.

Nesitanebetashru’s mummy, ushabtis, and coffins were discovered in tomb TT320 in Deir El Behari. Notably, her extensive Greenfield papyrus containing funeral text ranks among the longest known, held in the British Museum’s collections. In the 22nd dynasty, another Nesitanebetashru was the wife of the High Priest of Amun, Shoshenq, and the mother of Pharaoh Harsiese A. She held the role of Amun Chantress and is referenced on a Bes statue. Initially, her husband was wrongly identified as Pharaoh Shoshenq II.

Recently, a number of skilled Egyptologist has revitalized the previous idea that the renowned mummy known as “Unknown Man E,” discovered in the Deir el-Bahari cache, might indeed be Pentawer. This mummy stands out due to its unconventional embalming, which was done hastily without removing the brain and organs. It was then placed within a cedar box, which had to be crudely modified to accommodate it.

It’s hypothesized that Pentawer could have been rapidly mummified and put in an available coffin, likely by a relative, to ensure he received a proper burial. Additional DNA analysis provides support for this theory, as it indicates that the mummy was a son of Ramesses, sharing both the paternal Y-DNA haplogroup E1b1a and half of their DNA.

In 1980, researchers conducted a number of X-ray examinations on the remains of the New Kingdom of Egypt (1570 – 1050 BC) Pharaohs, including Siptah. The analysis revealed significant resemblances between the rulers of the 19th and 20th Dynasties of the New Kingdom and Mesolithic Nubian samples.

They also observed connections to modern Mediterranean populations from the Levant region. Harris and Wente proposed that this indicated a mixture of ancestry, given the northern origins of the Rammessides.

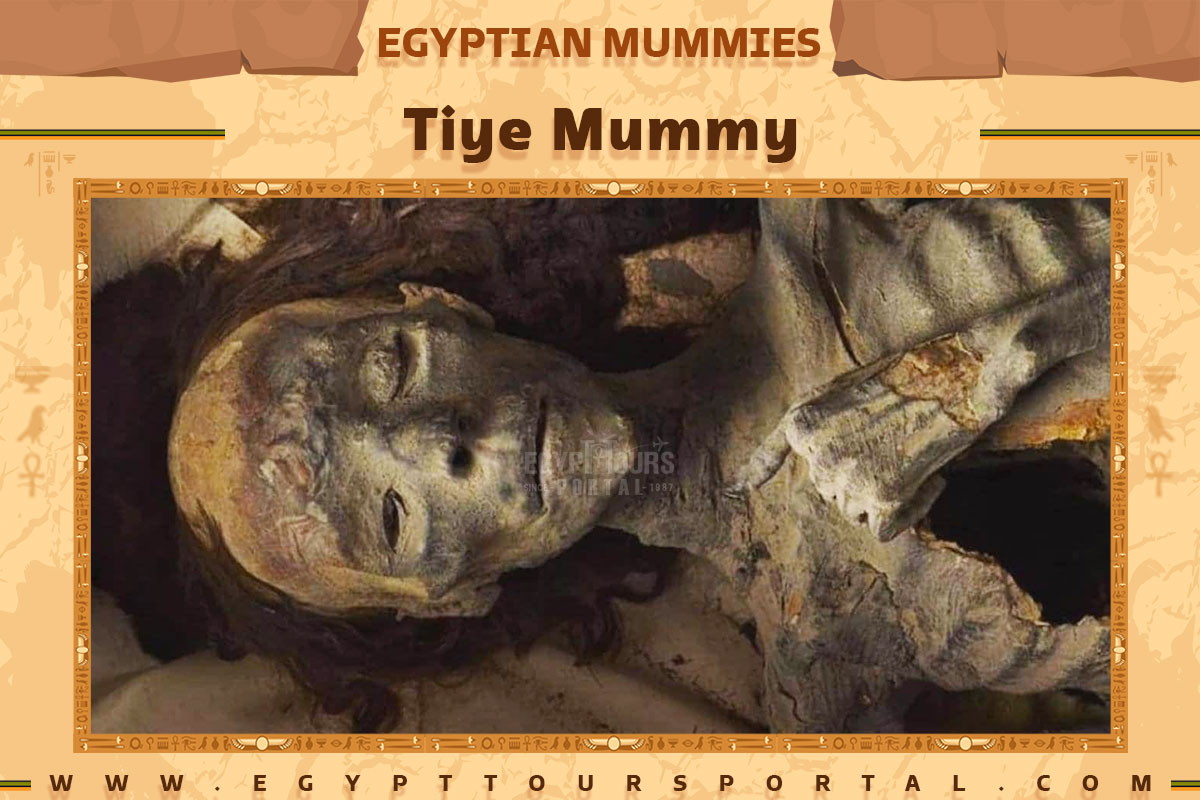

In 1898, three sets of mummified remains were discovered in a side chamber of Amenhotep II’s tomb (KV35). They included an older woman, a young boy thought to be Webensenu or Prince Thutmose, and a younger unidentified woman. The older woman was initially known as the ‘Elder Lady,’ and the other as ‘The Younger Lady‘. Some researchers speculated that the Elder Lady was Queen Tiye, but skepticism existed, including from scholars like Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton. A set of miniature coffins with her name and hairlock was found in Tutankhamun’s tomb. Microprobe analysis matched the hair with the Elder Lady’s, identifying her as Tiye. X-ray examinations in 1980 indicated her craniofacial profile aligned with Mesolithic Nubians.

In 2010, DNA analysis confirmed the Elder Lady as Queen Tiye, about 40-50 years old at death and 145 cm tall. DNA results in 2020 unveiled her mtDNA haplogroup K, with Yuya, her father, having Y-DNA G2a and mtDNA K. In 2022, the analysis suggested a genetic affinity with Sub-Saharan Africans among the mummies. However, complexity is noted in biological heritage interpretation. DNA analysis discrepancies among research teams have led to uncertainty about the ancient Egyptians’ genetic makeup and origins. In April 2021, her mummy was transferred from the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in the Pharaohs’ Golden Parade event.

Webensenu, belonging to the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt, held the title of prince. He was born as a son of Pharaoh Amenhotep II. Webensenu and his brother Nedjem are recorded on a statue of Minmose, who supervised works in Karnak. His life was tragically short, passing away as a child.

His final resting place might have been within his father’s tomb, KV35, potentially sharing space with Tiye and the Younger Lady. Artifacts like canopic jars and habits connected to him were also unearthed within the tomb. His presumed mummy remains in the tomb, hinting at his age of around ten at the time of his demise.

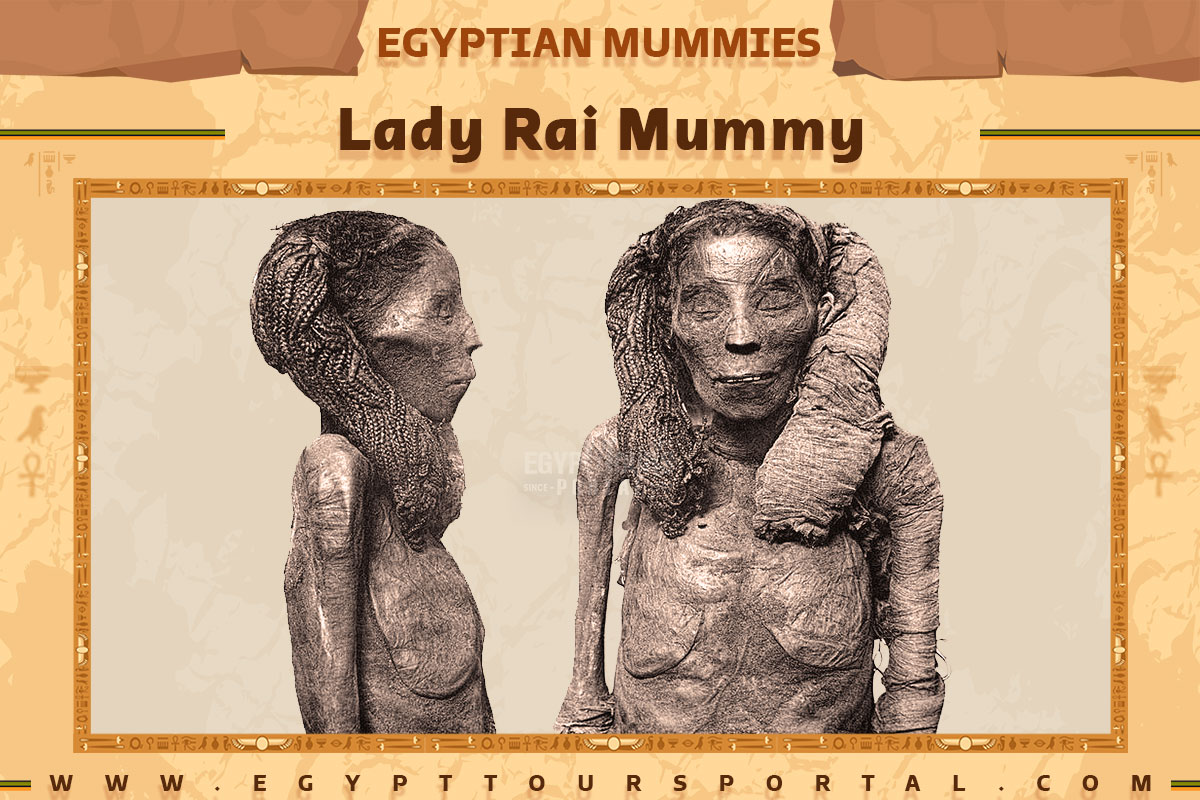

Lady Rai dates to the early 18th Dynasty and held the role of nursemaid to Queen Ahmose-Nefertari. In 1881, her mummified remains were found in a Theban tomb. She likely passed away around 1530 BC at an age of 30 – 40 years. The mummy was uncovered in 1909 who praised her embalming as a prime example from that era, noting her “Slim, gracefully-built” physique at 1.510 meters tall.

In 2009, a medical team’s CAT scan disclosed that Lady Rai’s mummy displayed a diseased aortic arch which makes her the oldest known mummy with atherosclerosis evidence. Interestingly, the mummy of Ahmose Inhapy was discovered within the outer coffin of Lady Rai.

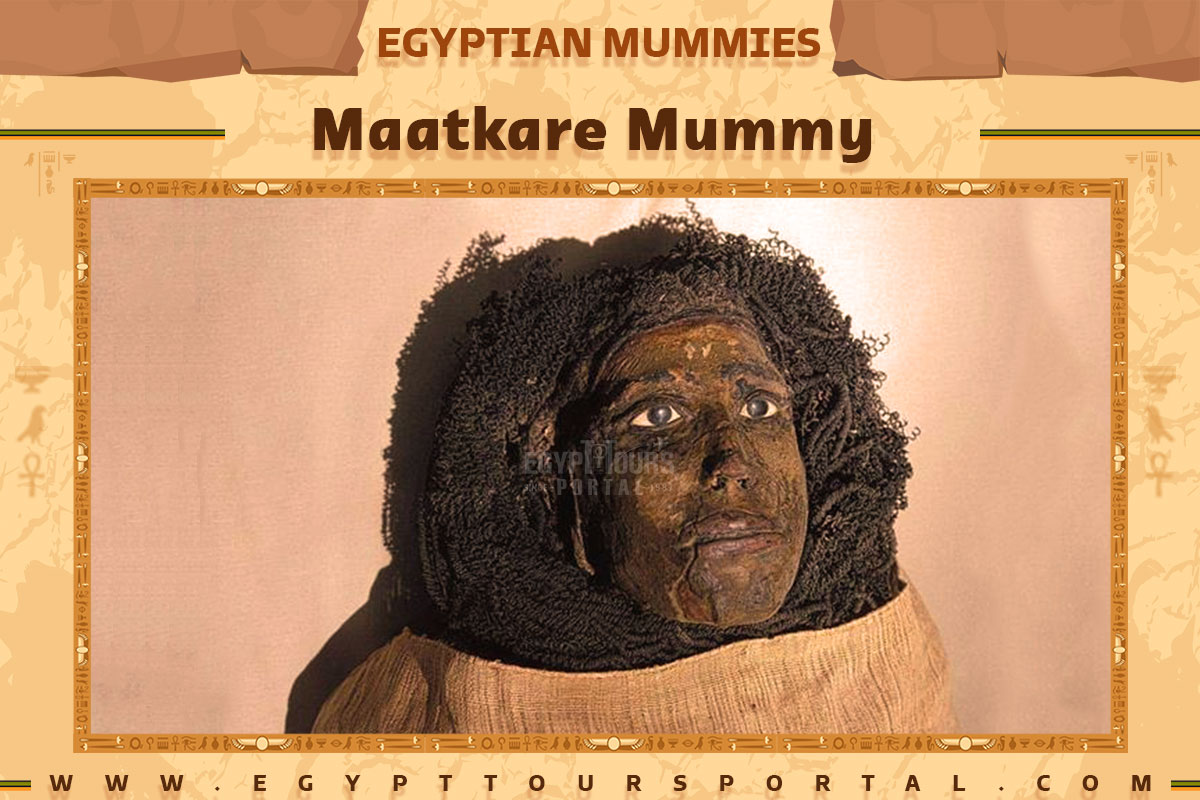

Maatkare (Mutemhat) was an esteemed figure in ancient Egypt, serving as a high priestess and God’s Wife of Amun during the 21st Dynasty. While her original burial site remains unknown, her mummified remains, along with her coffins, Shawabtis, and the mummies of her close family, were discovered in the DB320 cache in Deir el Bahari.

Initially, a small mummy believed to be her child turned out to be that of a pet monkey, underlining the supposed celibacy of God’s Wives.

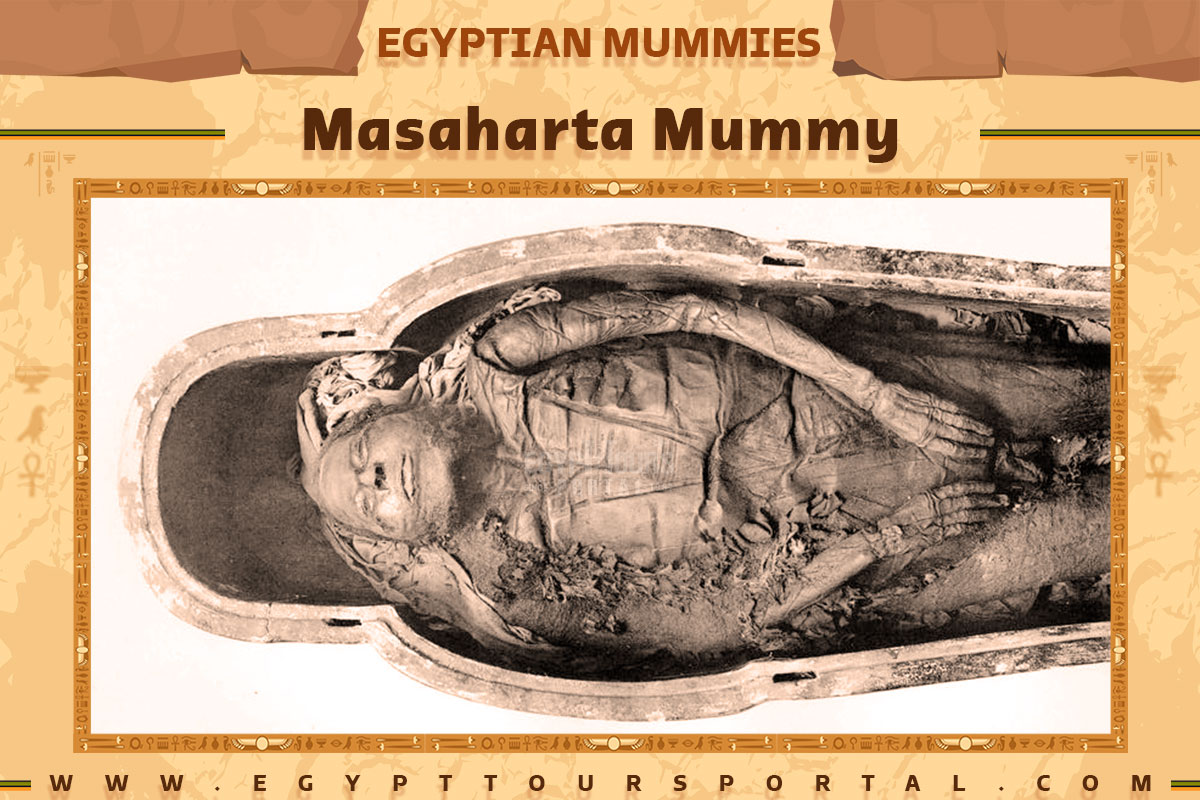

Masaharta was an ancient Egyptian high priest with a potential wife named Tayuheret and a possible daughter named Isetemkheb. He held the role of the God’s Wife of Amun during his reign, with his sister Maatkare succeeding him in this position. Masaharta’s inscriptions and statues can be traced to the Karnak temple of Amenhotep II and various locations.

Notably, he oversaw the restoration of Amenhotep I’s mummy during Smendes’ 16th regnal year. He is mentioned alongside Ankhefenamun in Theban. Although it is speculated that he might have passed away due to illness in el-Hiba during Smendes’ 24th regnal year, this theory lacks concrete evidence. His mummy, discovered in the Deir el-Bahri cache alongside family members, is currently housed in the Mummification Museum in Luxor.

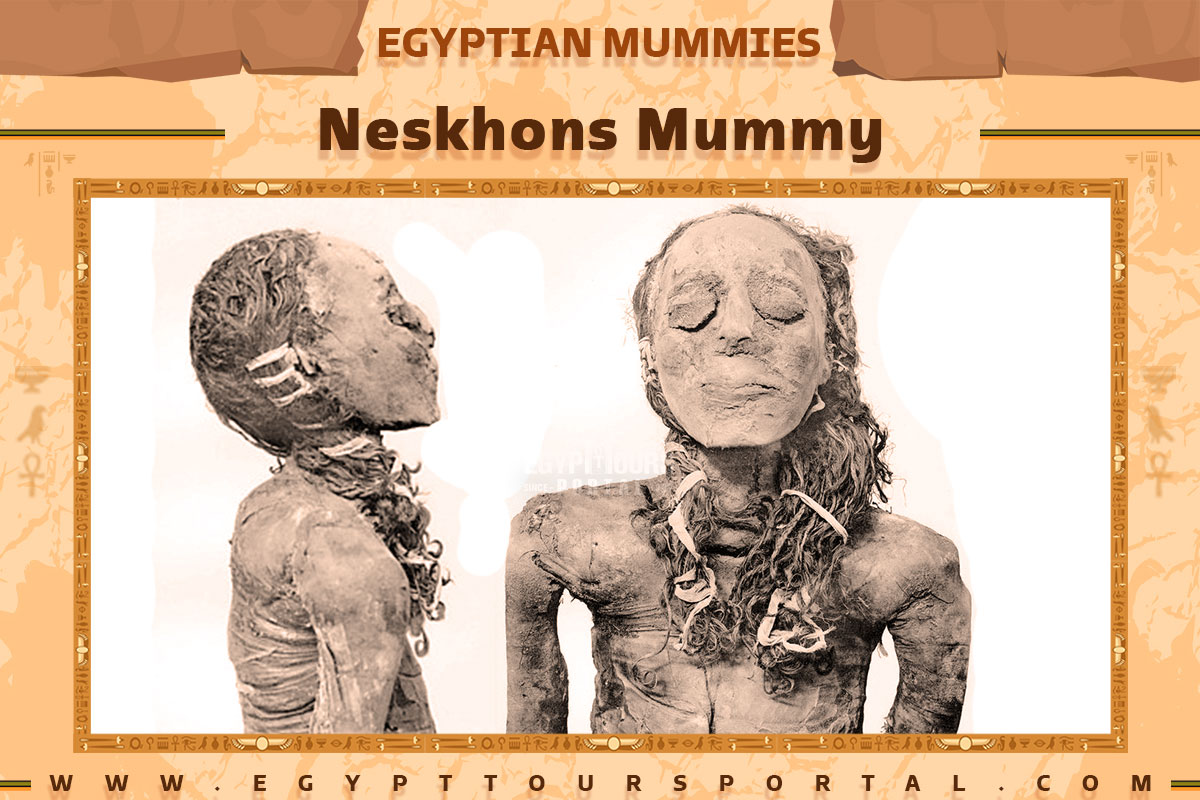

“Neskhonsou” was a noblewoman from the 21st Dynasty of Egypt, who had her mummy partly unwrapped by Gaston Maspero in 1886. She held esteemed titles like First Chantress of Amun and King’s Son of Kush. Despite her young age, her mummy lacked gray hair, indicating her youthfulness.

She might have been pregnant or giving birth when she died. The gold embellishments on her coffin were stolen in antiquity, and her heart scarab was taken by grave robbers but later recovered and now resides in the British Museum.

Pinedjem II served as High Priest of Amun from 990 BC to 969 BC, essentially controlling the southern region. Upon his death, he, his wives, and possibly one daughter, Nesitanebetashru, were buried in a tomb at Deir el-Bahri, above Hatshepsut’s Mortuary Temple.

The tomb’s discovery occurred in 1881. In the future, other rulers were also laid to rest there. This collective interment aimed to safeguard their remains from tomb robbers who had plundered their graves in the past.

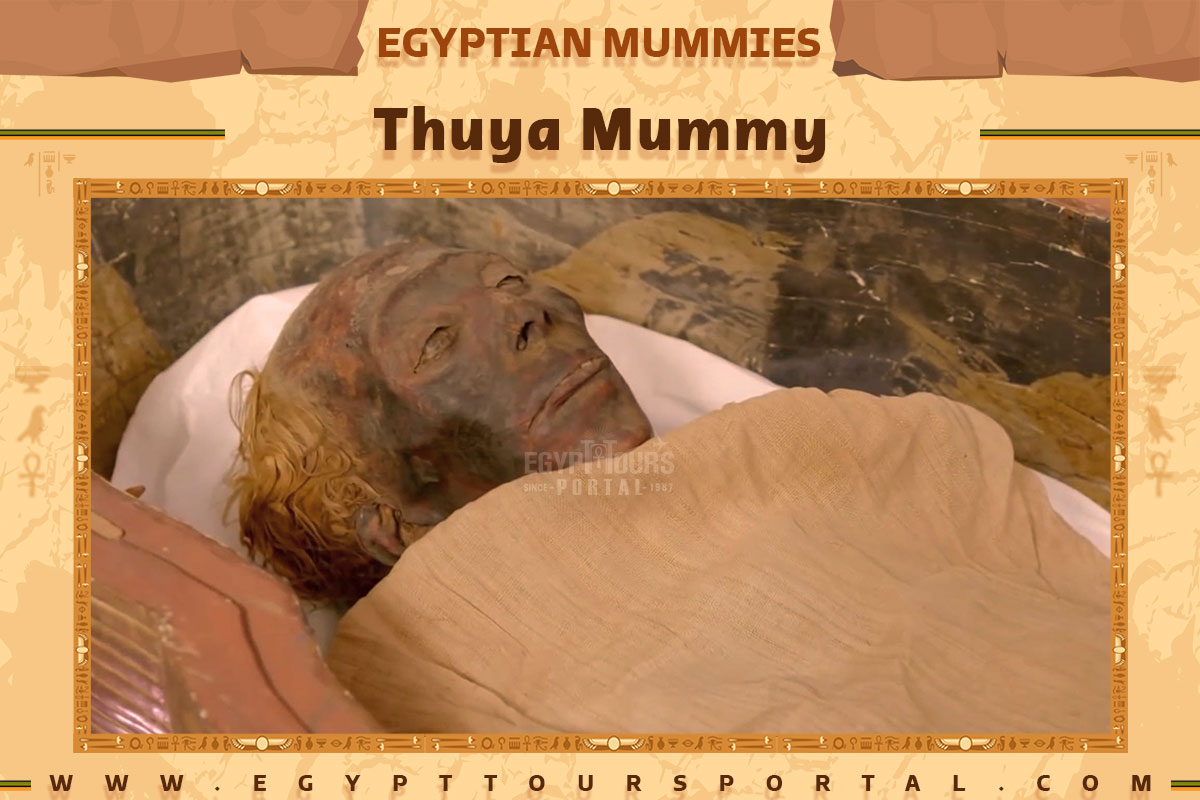

Thuya’s mummified body was discovered wrapped in linen and secured by bandages coated with resin. Gilded titles from gold foil adorned the bandages, revealing her status. The examination led by Grafton Elliot Smith described her as an elderly, small-statured woman measuring 1.495 meters (4.90 feet) in height. She had white hair and two piercings in each earlobe.

The arms were straight at her sides, and her hands rested on her thighs. Her body was filled with resin-soaked linen, and carnelian beads were attached to her embalming stitches. Gold foil sandals adorned her feet. Douglas Derry, assisting Smith, noted her age as over 50, which CT scans later estimated to be 50-60 years old. Her brain was removed, her nostrils stuffed with linen, and her face filled to appear lifelike. Dental issues were evident, and mild scoliosis was detected. The cause of death remains unknown.

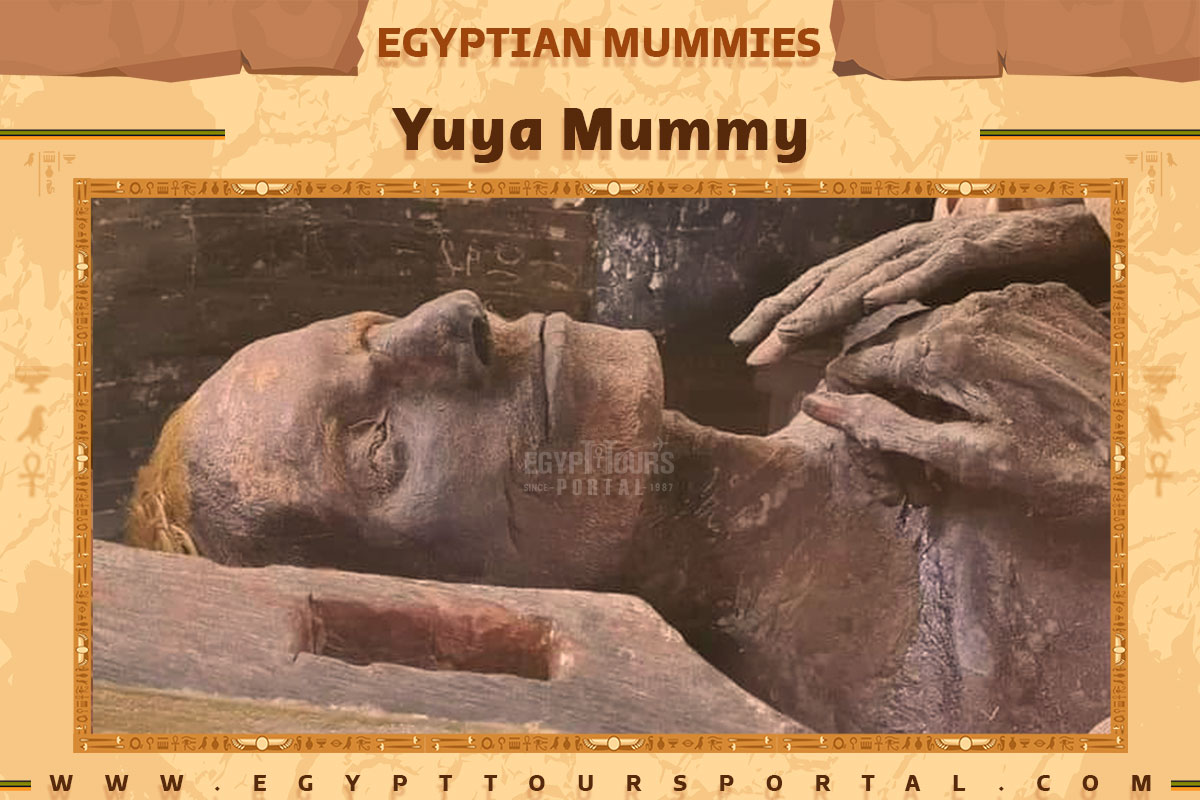

Yuya’s mummy was discovered with his torso partially unwrapped, exposing his embalming incision covered by a gold plate. Robbers had missed the plate but dislodged a necklace, leaving it behind his neck. His head wrappings were later removed before transportation to Cairo. Grafton Elliot Smith’s examination revealed Yuya as an elderly man with magical white wavy hair discolored by embalming, standing at 1.651 meters tall. His hands were placed under his chin, with a gold finger stall on his right little finger.

Linen packs were in his eye sockets and body cavity, with resin-treated packs in his mouth and under his skin for a lifelike appearance. CT scans estimate his age at death to be 50-60, showing great joint degeneration and tooth wear. Two layers of resin inside his skull were found, yet his cause of death remained undetermined. The positioning of sarcophagi suggested Yuya’s interment as the first, although his funerary mask indicated he might have outlived his wife Thuya.

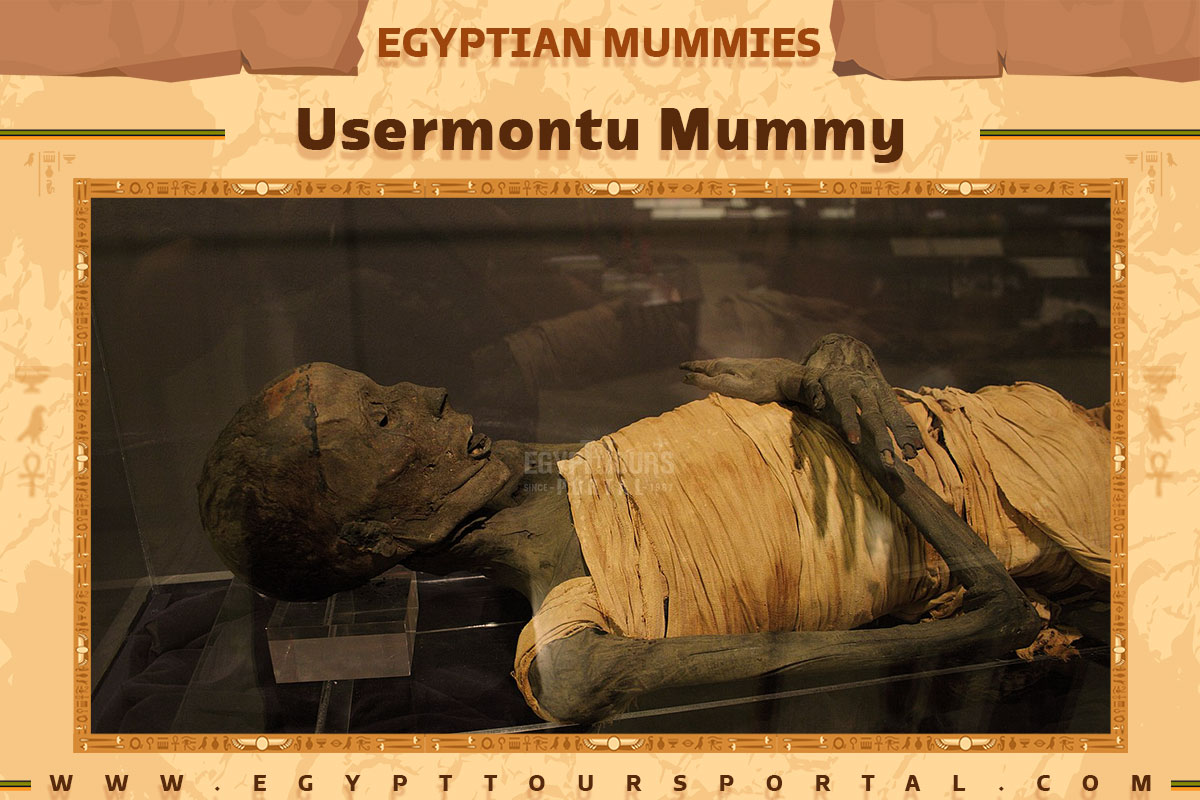

The Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum in San Jose, California, displays an ancient Egyptian mummy named Usermontu which means “Powerful is Montu“. The mummy is well-preserved and stands out for having an ancient prosthetic pin in its left knee. The museum acquired two sealed Egyptian coffins in 1971, one of which contained the mummy. The embalming style suggests that the mummy was likely an upper-class Egyptian male from the New Kingdom period (16th–11th century BCE).

The body was placed inside the coffin of a different person, the “Real” Usermontu from the 26th Dynasty, around 400 BCE. The origin of the coffin and mummy is unknown. Notably, the mummy’s left knee holds an ancient iron orthopedic screw, initially thought to be a modern addition. However, X-ray scans and further analysis revealed that the pin was inserted after the man’s death but before burial, held in place by organic resin. This operation aimed to preserve the body’s integrity for the ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs.

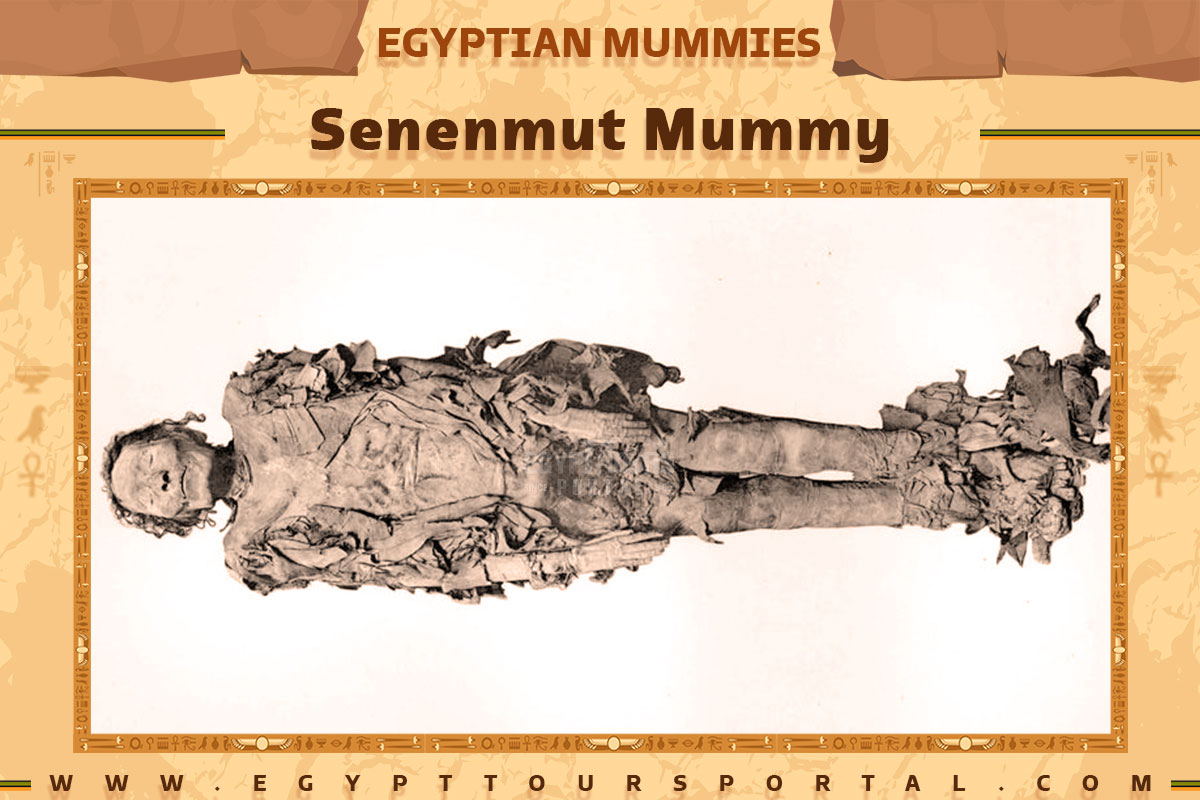

The search for Senenmut’s tomb has always been a mystery as his mummy was linked to the mummy of Queen Hatshepsut and he might have been buried with her because they could have been in love. The discovery of King Hatshepsut’s remains has raised questions about the location of her courtier Senenmut’s mummy. There’s interest in using DNA from bone or teeth to identify him among unidentified royal mummies. The intact tomb of his parents Hatnofer and Ramose, was found in their son’s courtyard. Senenmut’s tomb was explored in 1936, revealing a smashed sarcophagus that some believe might not have been used by him.

The hope is that if the sarcophagus was used, Senenmut’s mummy wasn’t inside during its destruction. DNA from Hatnofer and Ramose could identify him among unknown royal mummies, though the chances of finding him remain slim. Senenmut’s father Ramose was found as a skeleton and was likely not mummified, while his mother was initially mummified but has since degraded, aiding DNA preservation. Among male mummies from cache tombs DB 320 and KV 35, a possible candidate is a mummy labeled “Unknown Man C“. This mummy could belong to the early Thutmoside period, even during Hatshepsut’s reign. A box with Hatshepsut’s name was found in the king’s cache, potentially related to her mummy’s tooth discovery in KV 60. Senenmut had options for his burial, but his prominent tomb at Sheik Abd el-Qurna, where his parents were also buried, seems likely. There’s speculation that he might have died before Hatshepsut and been buried in her tomb, with later removals by Thutmosis III.

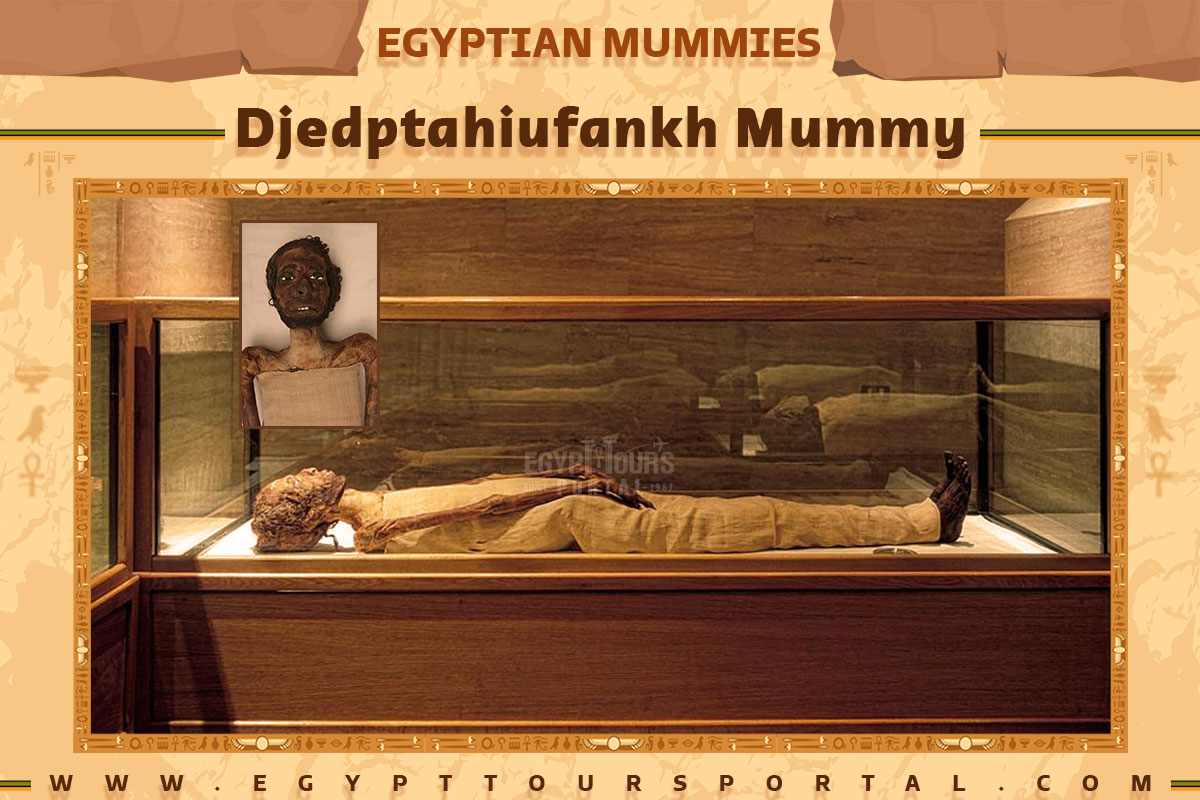

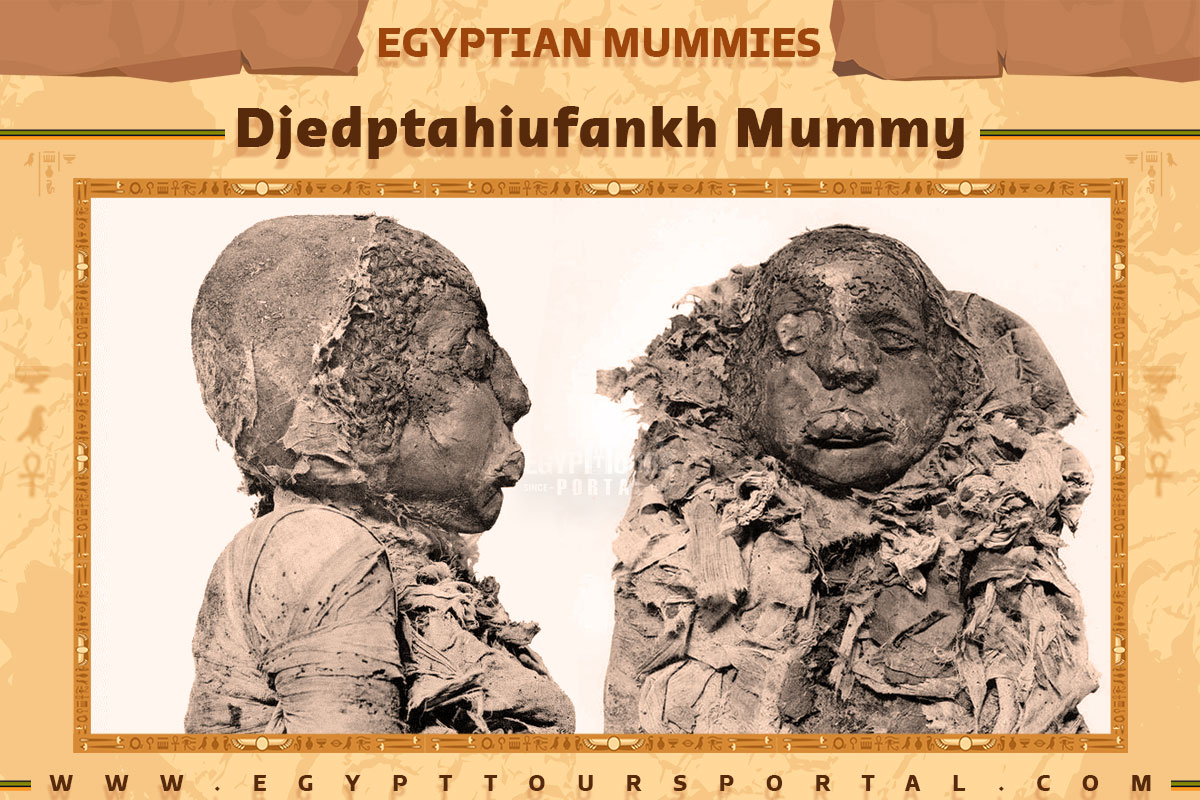

Djedptahiufankh (969 – 935 BCE) held positions as Second Prophet of Amun and Third Prophet of Amun during the reign of Shoshenq I of the 22nd Dynasty. Djedptahiufankh’s death occurred around the middle of Shoshenq I’s reign, as indicated by inscriptions on his mummy’s wrappings. Djedptahiufankh’s burial was well-preserved and included amulets, such as snake and lotus forms at the throat, a heart scarab on the chest, and stone amulets on the left arm.

Further examined the body in 1906, revealing additional stone amulets including a depiction of the baboon-headed god Hapi. A bronze embalming plate covered the incision used during organ removal. The mummified organs were placed within the body, accompanied by an amulet of Hapi. Thin gold rings adorned his fingers, potentially holding gold finger stalls in place.

Tayuheret “1054-1046 B.C.” was the wife of High Priest Masaharta, and similarities in their coffins suggest a close relationship. She’s believed to be the mother of Isetemheb as proven by her white hair indicates she lived a long life. Her mummification was poorly executed, leading to facial distortion.

Wax was used to prevent distortion, and she had a wax nose guard, stone eye, and wig covering her ears. Insect damage affected her forehead, similar to Maatkare and Duathathor-Henttawy-A’s mummies. Tayuheret’s body was documented in “The Royal Mummies,” and modern CT scans were used to assess her mummification quality. Her mummy, discovered in Tomb DB 320, chamber F, was found alongside Masaaharta and Maatkare Mutemhet. It’s speculated that DB 320 wasn’t her original burial site but a later relocation. The tomb, found in the Theban cliffs in 1881, held over 50 royals including kings and queens.

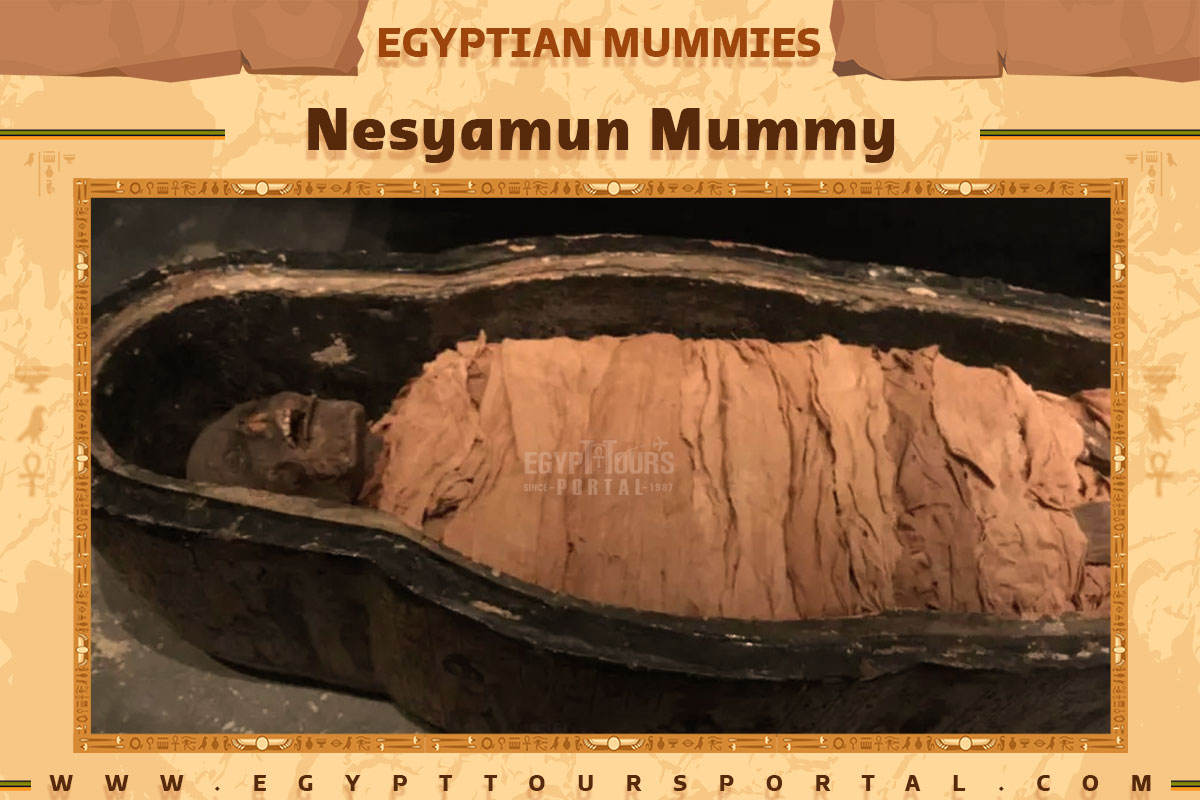

Nesyamun’s mummy was examined in 1824 and was wrapped in multiple layers of linen, surrounded by floral garlands, and adorned with a red leather ornament. It was covered with a layer of spicery and well-preserved. Bandages showed signs of recycling clothing, and his body cavity was filled with the same substance as the skin. His brain was removed through the right nostril, and organs through a left-side incision. Nesyamun’s X-rays in 1931–32, 1964, and 1989 revealed various details. The back of his skull was removed in 1824.

His teeth were worn, with some front teeth becoming peg-like, possibly from acidic fruit or over-cleaning. Gum disease but no cavities were found. His eyes showed nerve degradation, potentially linked to diabetes. He had O-type blood, a narrowed intervertebral disc with osteophytes, and signs of osteoarthritis. Filarioidea worms in his groin indicated filariasis, and atherosclerosis was seen in his arteries. Nesyamun was 5 feet 6 inches tall and died aged 40–50, and his cause of death is uncertain. His protruding tongue suggests an unusual circumstance; it’s speculated he died violently by strangulation, but his hyoid bone was intact. Another theory is swelling due to disease or allergy.